Image credit: Photo by Julie Millowick

SITE OF THE 1851 MONSTER MEETING OF DIGGERS

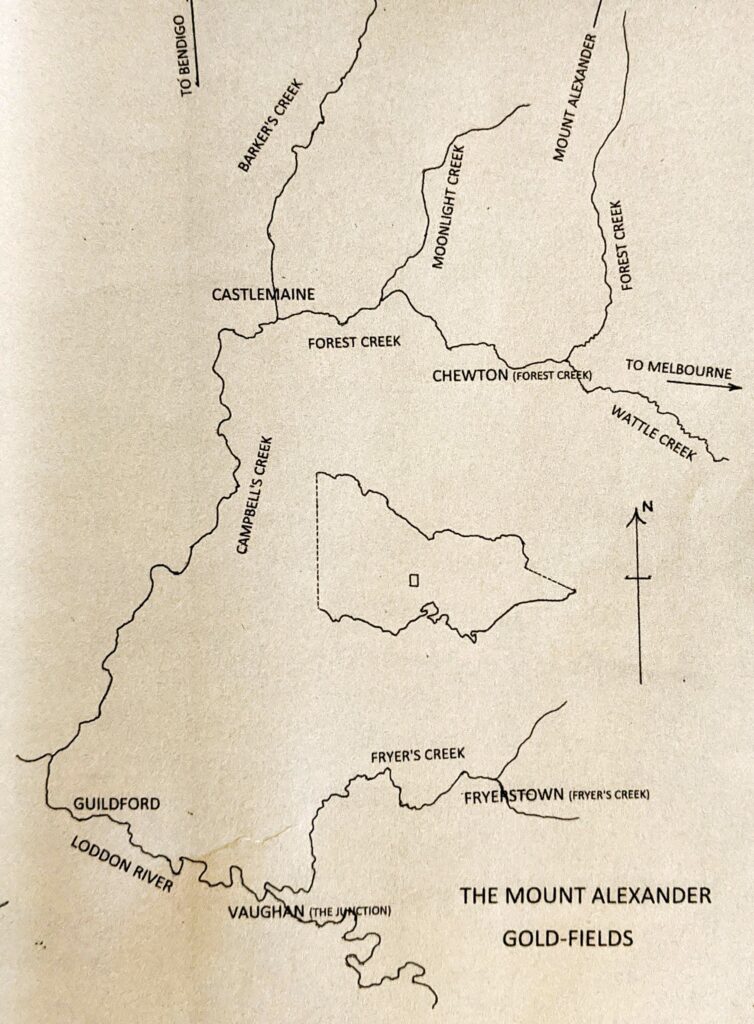

Forest Creek on the Mt Alexander goldfield in Dja Dja Wurrung country, was the richest shallow alluvial goldfield ever discovered and in 1851 it quickly became the epicentre of the Victorian gold rush. Now it is a quiet grassy valley in the Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park, But on 15 December 1851 15,000 gold diggers gathered there for the first mass protest meeting against the colonial government’s gold licence system. The Diggers’ defiance lead to Governor La Trobe backing down and rescinding the proposed doubling of the monthly gold licence fee and it set in motion a democratic protest movement that spread across the goldfields to the Red Ribbon Movement in Bendigo in 1853 and finally to the Eureka Stockade in Ballarat in 1854.

The Meeting site was listed in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR 2368) in 2017 to acknowledge the Meeting’s significant role in the early development of democracy in Victoria.

Unlike other 1850s gold rush sites, the landscape of the early diggings can still be seen here in the Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park Chewton. You can further explore the historic and Jaara Aboriginal sites across the central goldfields with Jan Wositzky’s audio tours, The Storytellers Guide to the Goldfields, found at janwositzky.com.au.

FOREST CREEK IS ON ABORIGINAL LAND

The Forest Creek goldfield was on the land of the Dja Dja Wurrung, who had lived there for thousands of years. They were driven from their land and their centuries old lifestyle was destroyed by squatters establishing sheep runs in the 1830/40s aided by the colonial government keen to develop the wool industry. The Dja Dja Wurrung knew there was gold there – they called it kara kara – but they left it lying in the ground because it was of no use to them. It was too soft to make tools and weapons and too heavy to carry.

Historian Fred Cahir, in his book Black Gold, tells how the Dja Dja Wurrung who were still there at the start of the gold rush, lived by adapting to the unwanted new conditions. They had a significant role in tracking and guiding prospectors, who relied on them for direction in what many must have seen as a trackless wilderness. They also fossicked for gold, worked at various jobs on the goldfields and in neighbouring farms, traded artefacts including possum skin cloaks, sold sexual services and staged corroborees for paying audiences.

Some Aboriginal people were employed as uniformed native police on the goldfields.

The Dja Dja Wurrung’s traditional rights to the land of the gold rush were not recognized until 2013 when the Victorian Government formally granted them native title to the 266,532 hectares of their stolen land that encompass that area.

LIFE @ FOREST CREEK IN EARLY 1850s

Forest Creek on the Mt Alexander goldfield in Dja Dja Wurrung country was the richest shallow alluvial goldfield ever discovered and in late 1851 it became the epicentre of the Victorian gold rush.

Alluvial gold is the gold that has been freed from the matrix of rock (usually quartz in the Forest Creek area) by the weathering of ages and then washed and transported by water. Because it is heavier than other detritus of gravel and stones, gold sinks to the bottom when it is washed down into the creeks and flats. Because it is relatively close to the surface the gold is easily accessible to all, making alluvial mining the most democratic of mining methods.

On 8 September 1851 a letter in the Argus newspaper announced the discovery of gold at Mt Alexander and thousands abandoned their jobs and homes in cities, towns and stations to rush to the diggings. This was a ‘domestic’ rush of people already living in Australia. The boats from Europe did not begin arriving until later in 1852, when more than 90,000 immigrants arrived after having heard of the riches at Forest Creek. The Chinese did not arrive in any large numbers until 1854.

Robyn Annear, in her book Nothing but GOLD, reports that Forest Creek, at the base of the Mt Alexander range, was the initial focus of the rush with 2,000 gold diggers there in the first week of November ‘picking out easy fistfuls of gold. … ‘Using only their penknives, diggers prise gold from the topsoil – enough to fill their pockets and pint-pots to over-flowing’. Over the following weeks thousands more arrived and by mid-December an estimated 25,000 people were on the Mt Alexander goldfield. The gold diggers spread out from Forest Creek across a wide area and Governor La Trobe reported to London, ‘Right and left throughout the whole region gold is found to exist…. The field is reported to be illimitable … each last found diggings apparently eclipsing all before it.’ In December he wrote that the successful search for gold in the area ‘has been such as completely to disorganize the whole structure of society’.

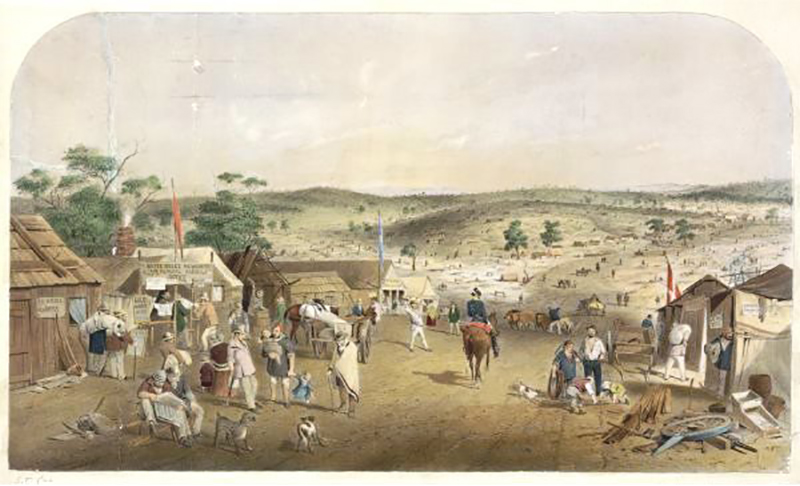

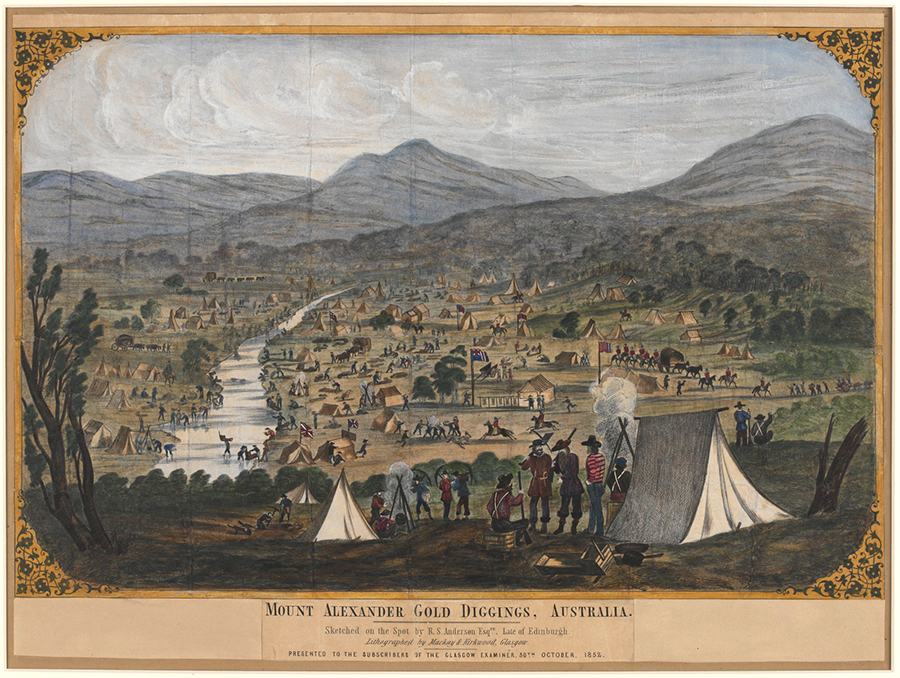

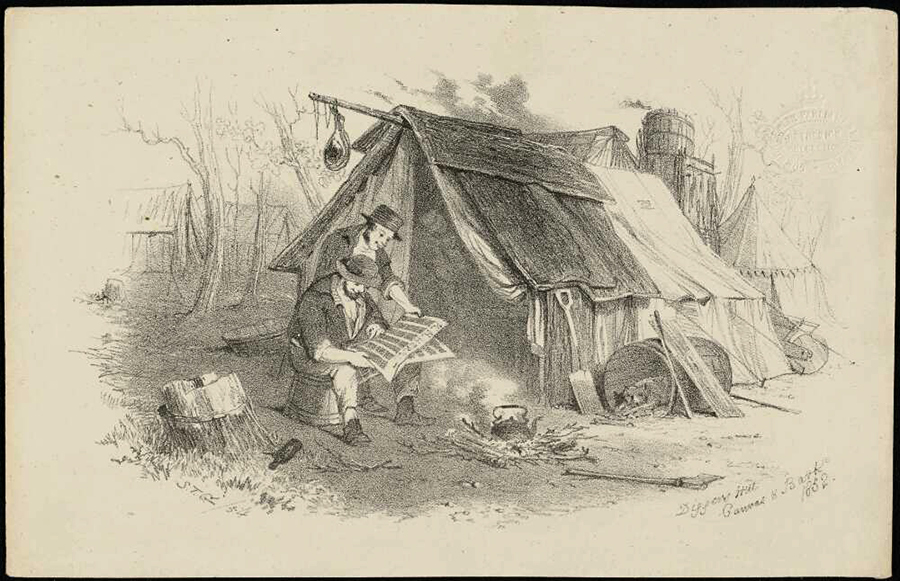

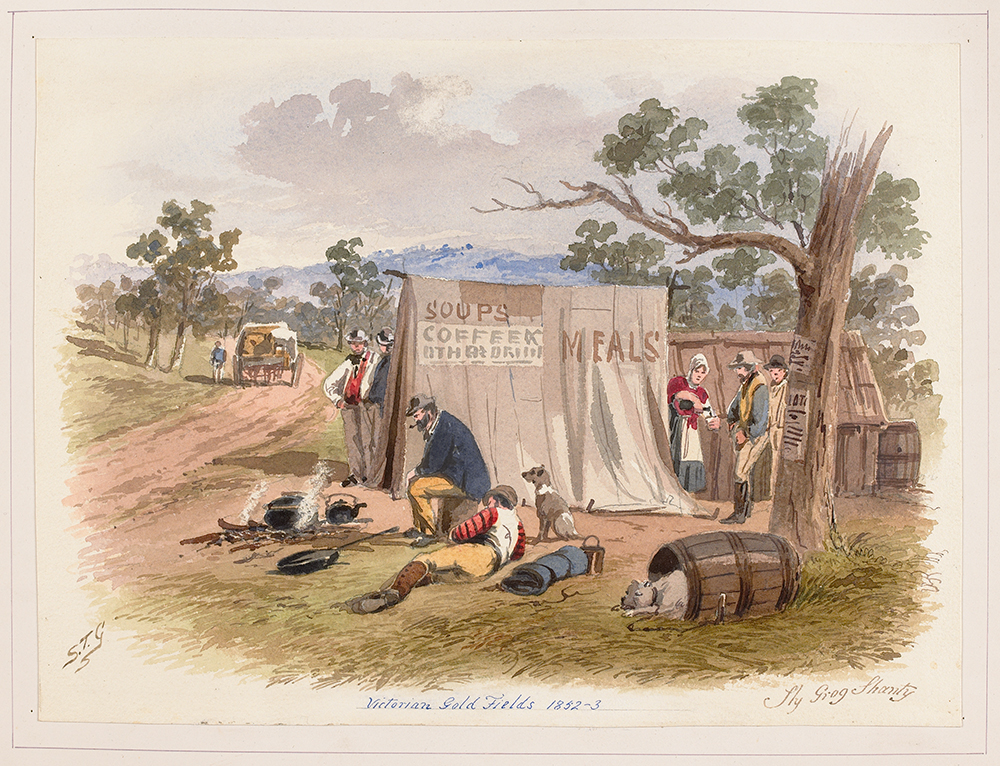

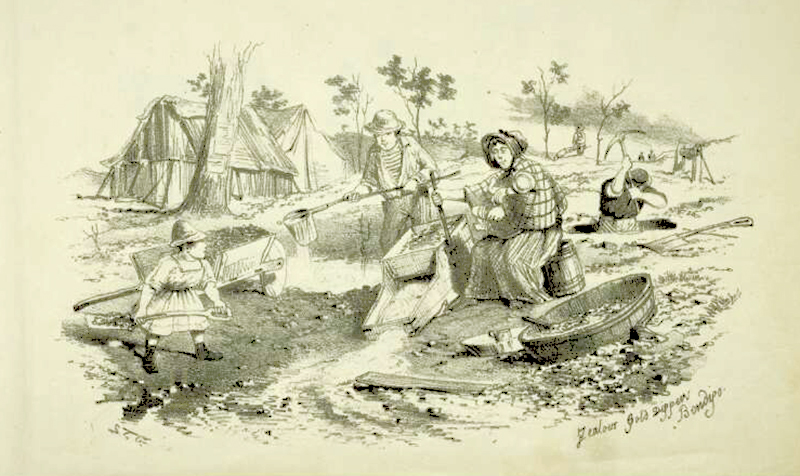

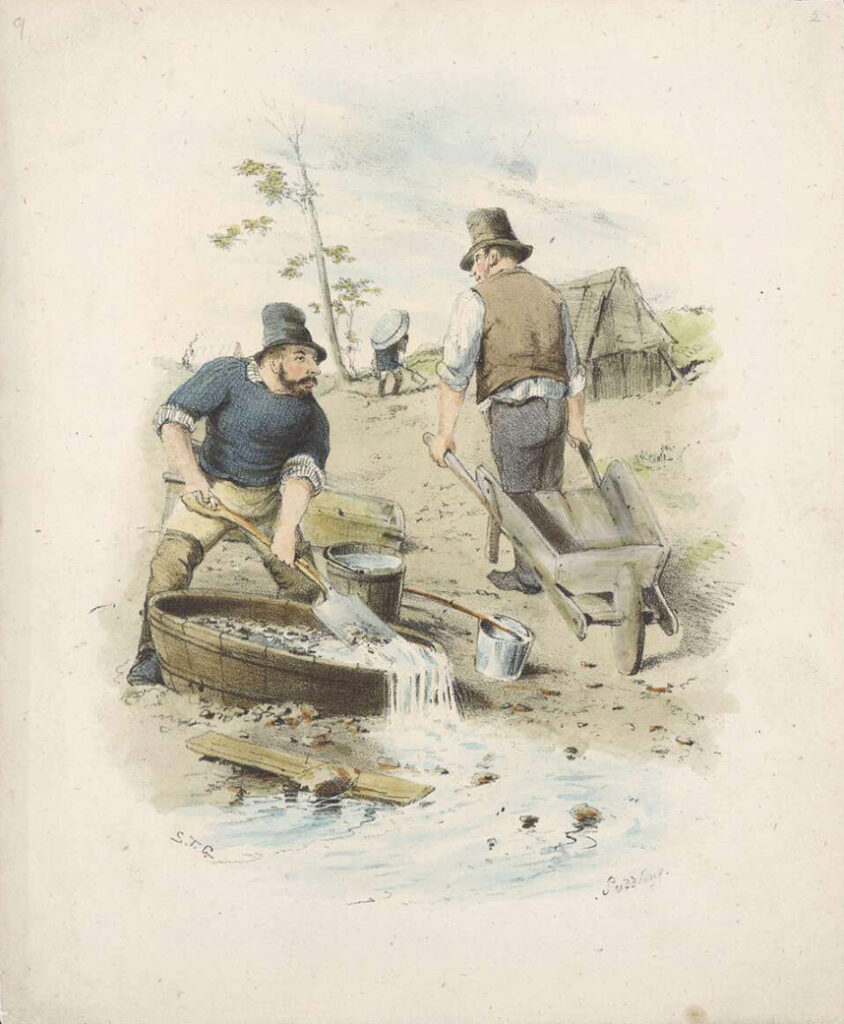

The drawings made by the many artists who were at the goldfields in the early 1850s, provide a visual record of how the gold diggers lived and worked. It is a record mainly of white men with fewer images of the many women living there – estimated at around a quarter of the population by January 1852 – and even fewer images of the Aboriginal people who were there. The drawings mostly show a rather romanticised view of what would generally have been unsafe and unsanitary conditions in basic camps with minimal facilities for cooking, washing and waste disposal.

ROBERT ANDERSON

Drawn on the spot by Robert Anderson. Lithographed by Mackay & Kirkwood Glasgow and presented to the subscribers of the Glasgow Examiner in 1852. ( La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria)

Anderson’s drawing shows Forest Creek in 1851 as a very busy area, crowded with the tents, fireplaces and mine shafts of people digging, panning in the creek for gold and working at their claims. His drawing also shows mounted police intervening in an altercation, several permanent structures plus delivery wagons and a departing gold escort with a covered wagon flanked by armed mounted police.

S.T. GILL

Many of S.T Gill’s drawings of life at the Mt Alexander goldfield in the early 1850s are held in the Castlemaine Art Museum. Others are in the Picture Collection of the National Library of Australia and the La Trobe Picture Collection of the State Library of Victoria, where they can be viewed online.

Gill’s early drawings of the gold diggers in 1851/52 show clearly how they lived and worked, including some depicting women and children.

Diggers outside their hut reading a newspaper – their only source of news. Note that Gill has included the digger’s tools, the cooking fire and food suspended outside the hut to keep it safe from dogs and ants.

The sly grog tents, like this one, were labelled as selling coffee or lemonade and were often run by a woman.

Drawing of the whole family at work. Note the woman holding her baby while she rocks the cradle to wash dirt for gold. In the foreground a child shovels the dirt and further back a young man pours the water to go into the cradle, while a man digs for more dirt to wash.

Drawings show diggers washing dirt for alluvial gold using cradling and puddling equipment.

DAVID TULLOCH & THOMAS HAM

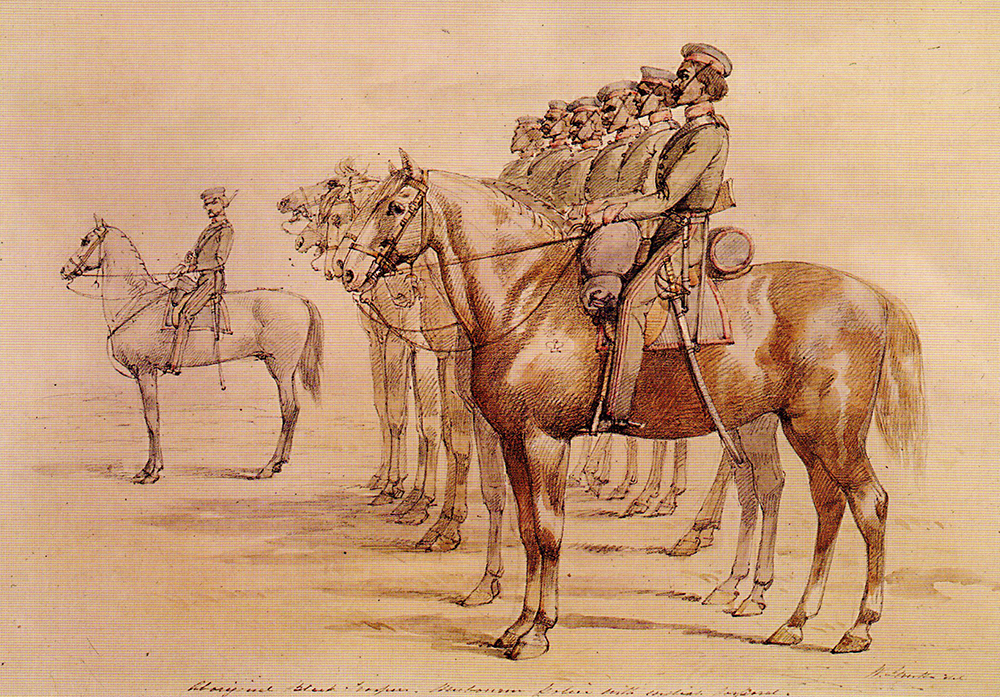

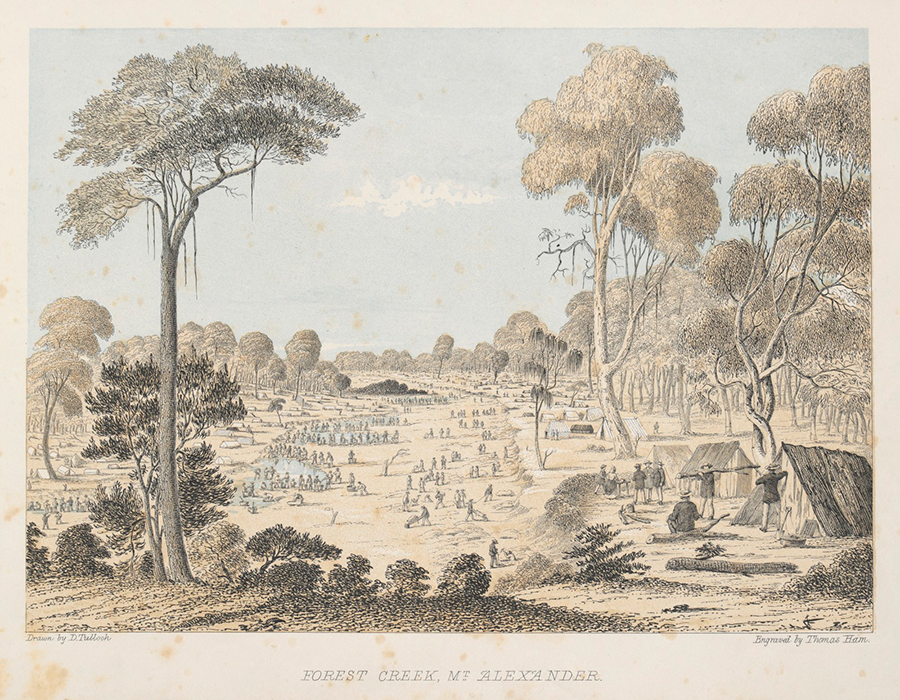

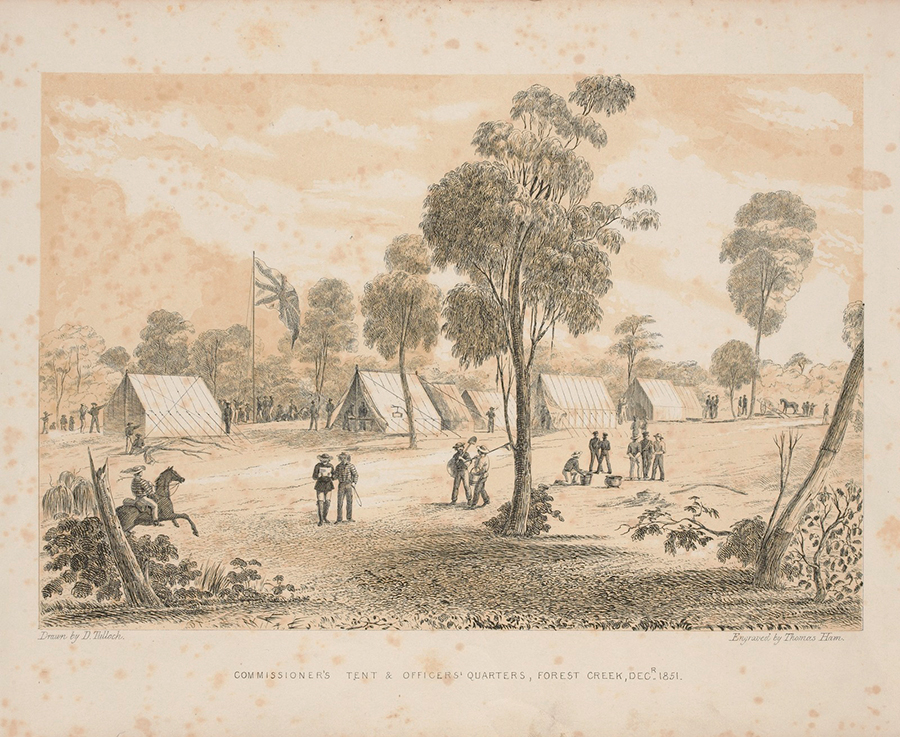

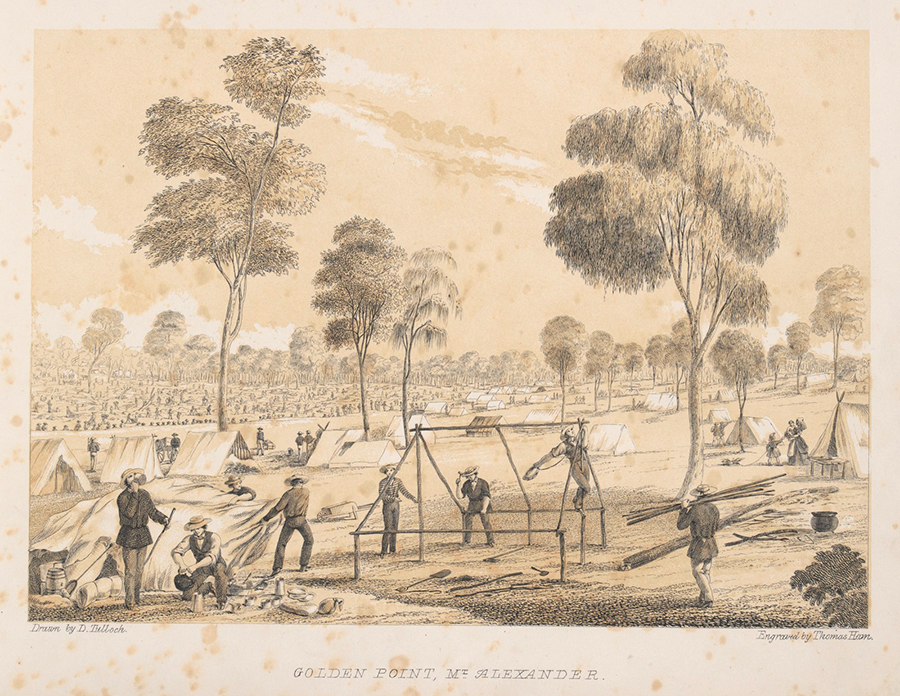

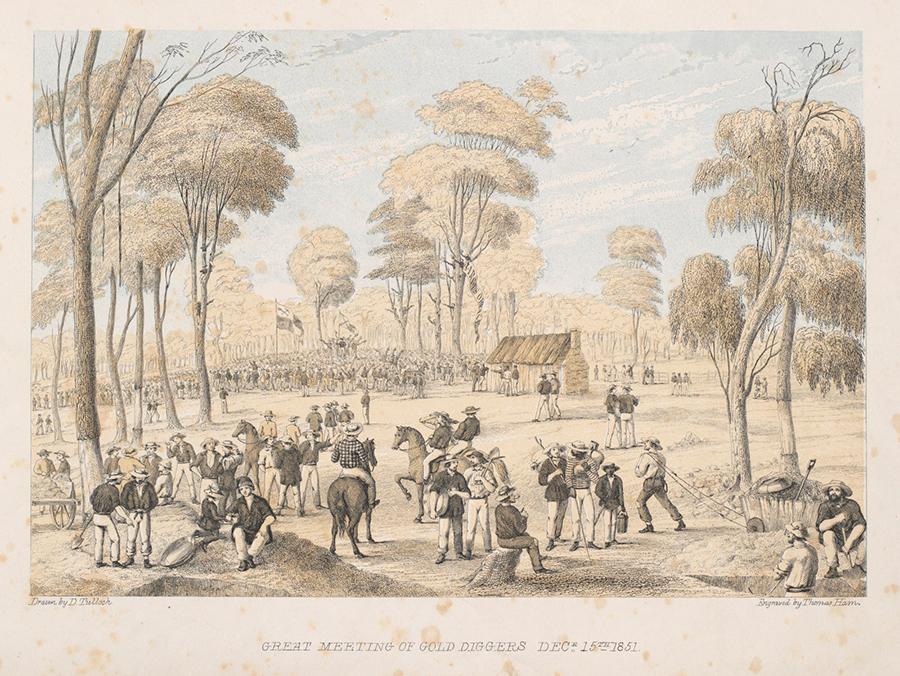

In 1851, soon after gold was discovered, David Tulloch began drawing many scenes of life at Forest Creek, including the Diggers’ Monster Meeting, the Commissioner’s tent and officers’ quarters and the erecting of tents, as well as the general landscape. In 1852 Thomas Ham made lithographs of some of Tulloch’s early drawings and accompanied them with his descriptions of the scenes.

‘Upwards of a mile of the Creek is presented in this engraving; and the occupations of the miners are various. Some of the men are engaged in what is termed ‘surfacing’, – collecting the surface soil, and washing it, from which a large return is acquired; others, where it is necessary to go deep into the earth, dig a shaft of thirty feet, or upwards, and on arriving at the gold stratum, commence under mining, – a rather perilous pursuit. When the water failed in the creeks, and holes, as summer advanced, the miners resorted to what is called ‘nuggetting’, by sinking to the layer of gold, and then with a penknife extracting it from the soil with ease; they were able to make about an ounce per diem. ‘Fossicking’ is another plan of gold seeking; this requires only a tin dish and a little impudence. The fossicker goes to the holes of those who have thrown away the surface, and without the trouble of digging, fills his dish, takes it to the water, and the general result is a good share of success. Some others are in the habit of fossicking during the night, ascertaining which holes yield abundantly, they take a turn in them while the owners sleep, thus enriching themselves by appropriating the labours and profits of the less cunning and watchful.

The geological formation of the gold fields is very much alike in all the localities where the precious metal has been found.

At Red Hill, in the vicinity of the scene of this engraving, there were great findings. A horseman, galloping along, turned up a good-sized nugget; and the news soon spread. The surface soil was very rich; and the first washers gained a considerable reward for their labour. A red earth was below (where the hill was named) from which also a yield was obtained. Next, a deposit of sand stone was found, varying from one to four feet in thickness; underneath this was a hard white pipe clay, with boulders of quartz, beneath which the richest yield of metal was found deposited in a kind of steatite or what the miners call brown clay, along with indentations of the slate rock, which formed pockets for it to lodge in. Generally the gold was met with along the surface of the slate, on which account many dug for this as the shortest road to fortune, and as soon as they approached the slate, began to undermine. Numbers of inexperienced hands have been known to heave the gold out of the holes in their eagerness to reach the bottom, and when asked what they were seeking, have been stupefied with astonishment to find they have been for days throwing away the object of their labour.

It is worthy of remark that at the Red Hill, the first excavators satisfied with the surface yield, betook themselves to the next famed locality, while others came and commenced where they had left off, and found better returns than the first seekers. There is great restlessness among the miners, a constant shifting of their position, and exchange of holes by purchase; and as a general fact, the latter tenants make more than the original holders; moreover their success is very unequal; a man may make but a small return, though he goes deeper than a neighbour almost adjacent to him, who is literally gathering gold. The inequalities of the distribution is remarkable, and gold-finding is a perfect lottery – at least, with the present imperfect knowledge of the nature and cause of this inequality, men are unable to pitch upon a spot with anything like scientific decision, and hence the whole work is one of hazard.

The stringy-bark trees to the left of the engraving, with the honey-suckle below, it, contrasts with the gnarled and twisted red gum, between the tents on the right, and with the white gum, a little in advance. The other trees are the shiae, with its pendant leaves, the light wood, the cherry tree and the mimosa, which, by their diversity, render our forest scenery charming.’

Drawn on the spot by D Tulloch. Engraved by Thomas Ham 1852. Accompanied by these words. (State Library of Victoria)

‘There is an air of quiet in this engraving, not perceived in any other scene we have portrayed; this is the general feature of the neighbourhood of the Chief Commissioner’s Quarters, with the exception of the earlier days of the month, when licenses are issued, and those days appointed for receiving gold to be forwarded to Melbourne by the Government Escort. The large tent, near the centre, was appropriated to this purpose, and that to the left to the use of the Licensing Commissioner. When our artist was on the spot, the Police Force was inefficient, and wholly engaged on duty at the Chief Commissioner’s, consequently there was a general feeling of insecurity; but since that period many desirable changes have been effected – large bodies of police have been placed on duty, and the Government is now erecting wooden buildings in various parts of the Diggings, for the accommodation of its officers; and more energetic measures have been taken in the appointment of additional Assistant Commissioners (who are also magistrates), with large bodies of Pensioners as Police under their direction, – thus the diggers are enabled to carry on their operations, and feel that their lives and property are as secure as in a well-ordered town. Roads traversing the different Diggings are also in progress, which, it is obvious, will greatly facilitate inter-communication.’

Drawn on the spot by D Tulloch. Engraved by Thomas Ham 1852 accompanied by these words (State Library of Victoria).

‘There is a diversity of employments, the auriferous earth is being conveyed in barrows on men’s backs, and by a variety of vehicles, to the washers … a fair exhibition of the life, and enterprise, the self-denial and labour, which have always accompanied and distinguished the miners.

The tent to the left of the Point, with the Union Jack flying, is the store of Mr Black. There are many others established in different localities, and the stimulus of the commerce is so great, that besides an abundant supply of necessaries the luxuries of life are not wanting. At one time, when certain delicacies were not to be had in Melbourne, they were abundant at the Mount. The price of provisions is not higher than might be expected, from the large sums paid for carriage, though, unquestionable, the speculation is profitable to the storekeepers, and the low rate at which they purchase gold, and advanced price of manufactured articles or necessaries of life, must be greatly enriching them. In every respect then, there appears to be a full hope for both the working man and trader, that for years to come any number of people may find gold over the vast plains which are now proved to be auriferous, and that the enterprise of business men will provide every requisite for the diggers at a fair profit, so that there will be no failing of riches to the labourers, the traders, and the speculator.’

The exceeding richness of the Mount Alexander diggings, and the extraordinary success of many of the miners, led the Government to issue a proclamation, raising the licence from thirty shillings to three pounds. As soon as these intentions became known, a public meeting of all the miners was convened, and took place on the 15th of December, 1851.

This resolve of the Governor and Executive Council was injudicious, since, in New South Wales, the Government proposed to reduce the fee to 15s.; and among the miners in Victoria, dissatisfaction was rife, on account of the apparent disregard by the Government of the wants and wishes of the people engaged in the gold diggings, and because of the absence of all police protection, while there appeared to be no effort made to remedy this defect. Indignation was, therefore, unequivocally expressed at the several diggings meetings which were held, and at which it was resolved to hold a monster meeting.

The ‘Old Shepherd’s Hut’, an outstation of Dr Barker’s, and very near the Commissioners’ tent, was the scene chosen for this display. For miles around work ceased, cradles were hushed, and the diggers, anxious to show their determination, assembled in crowds, swarming from every creek, gully, hill, and dale, even from the distant Bendigo, twenty miles away. They felt that if they tamely allowed the Government to charge £3 one month, the licensing fee might be increased to £6 the next; and by such a system of oppression, the diggers’ vocation would be suspended.

It has been computed that from fifteen to twenty thousand persons were on the ground during the time of the meeting. Hundreds, who came and heard, gave place to the coming multitude, satisfied with having attended to countenance the proceedings. The meeting ultimately dispersed quietly, thereby disappointing the anticipation of those who expected, perhaps even desired, a turbulent termination. The majority determined to resist any attempt to enforce this measure, and to pay nothing; but, happily, they were not reduced to this extremity, since his Excellency wisely gave notice that no change would be made in the amount demanded for the license.

As a moral demonstration, nothing could be more admirable. It proved that, as a body, the Miners were not a demoralised and treasonable set of men. While jealous of their rights, and prepared to withstand oppression, they were not desirous to evade any just claim of the Government; they were willing to submit to equitable taxation. The order, diligence, and industry of the Miners are remarkable. Among the sixty or seventy thousand men, congregated in engagements differing widely from the ordinary pursuits of life, some may be expected to exhibit irregularities which, in a more civilised position, they probably would not permit themselves; still the good order is surprising, infractions of the law being few, and exceptions to the rule.

The meeting brought fully into view this state of things. There were few who did not cease from work to attend, yet no disorder or intemperance was seen. The trees in this locality are chiefly stringy bark; some of them are peeled of their covering, as many persons prefer erecting bark huts to living in comfortless tents. The various groups, and costumes of the men, are characteristic of our gold digging community.’

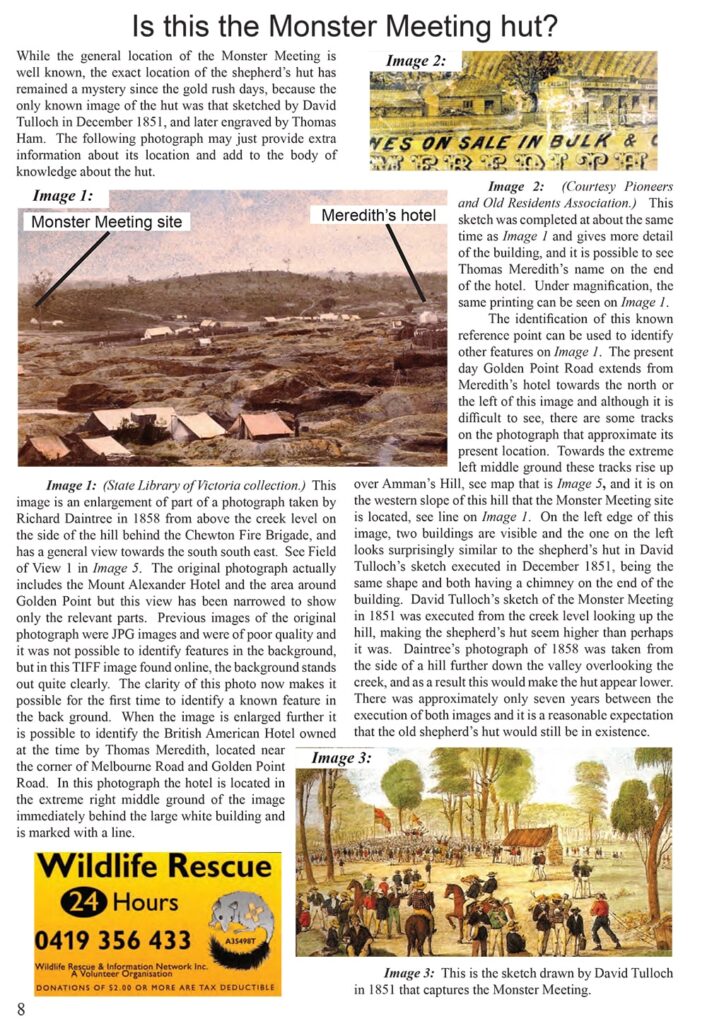

WHERE DID THE DIGGERS MEET IN 1851?

Over the years there has been some growing interest in locating the exact site of the 1851 Meeting in the contemporary landscape by identifying the site of the long gone bark shepherd’s hut – a difficult task after 150 or so years.

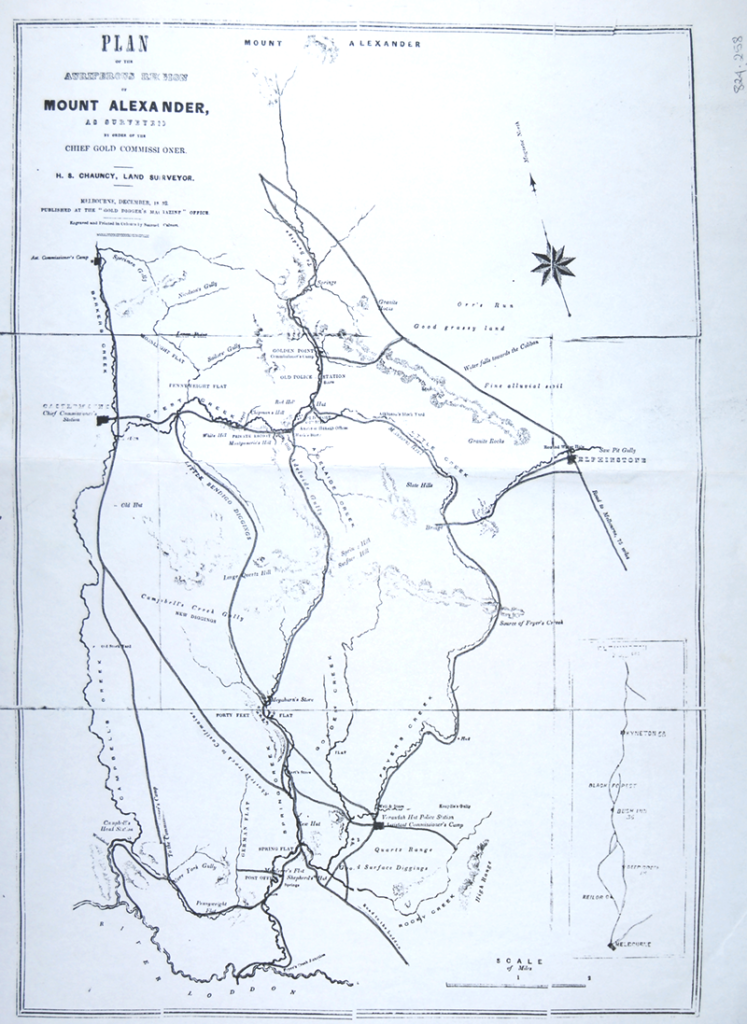

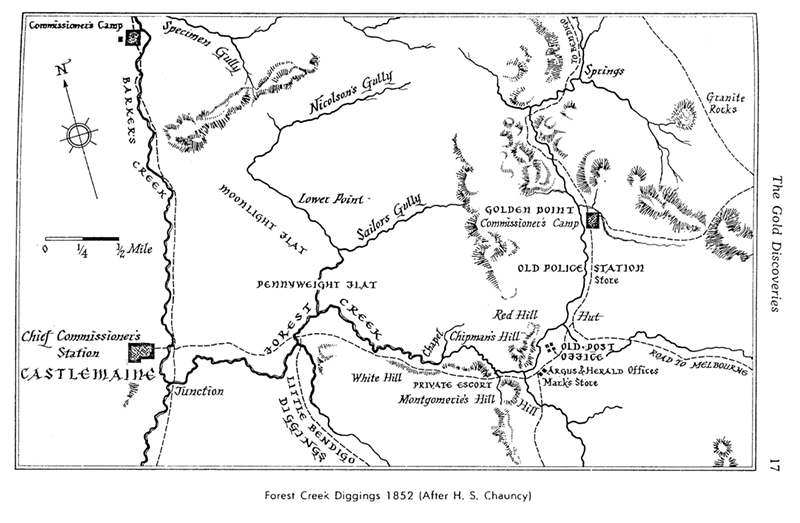

There were two large meetings of gold diggers at Forest Creek in December 1851 – the Monster Meeting on 15 December, near the old bark shepherd’s hut, and the earlier meeting to organise it on 8 December, near the old Post Office. The locations of both the old Post Office and the old bark shepherd’s hut – are clearly indicated by 1852 maps of the area drawn by Land Surveyor H S Chauncy for the Chief Gold Commissioner.

According to a report in the Argus (12 December 1851), some 3,000 persons gathered for the 8 December meeting …near the post-office…,which is clearly shown on Chauncy’s maps.

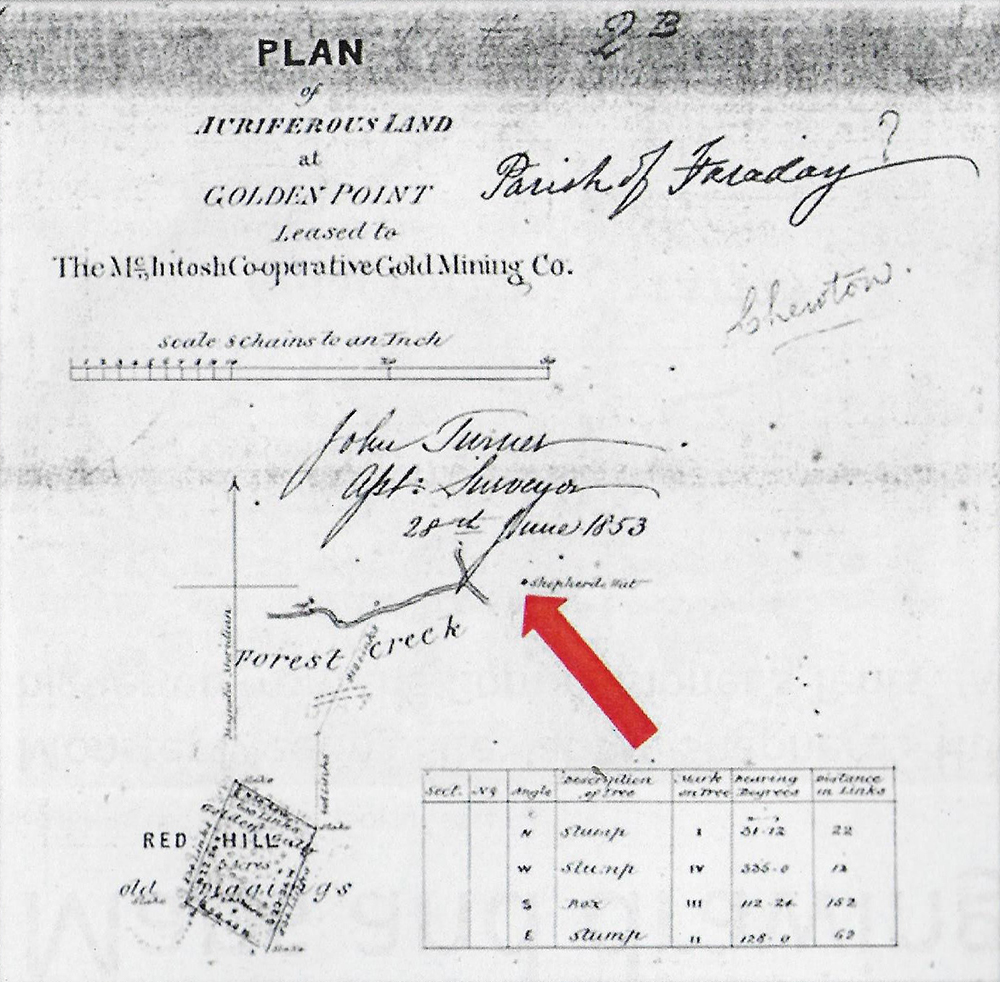

The location of the bark shepherd’s hut shown on Chauncy’s map is also shown on an 1852 lease survey plan for the McIntosh Co-operative Gold Mining Company. It shows the hut at an estimated 70 metres from the Creek. The position was described in the Argus (18 December 1851 p2) as … Shepherd’s Hut near the Post Office …. About one mile higher up from the Commissioners’ Tents.

In 1994 a map on the Council’s Tourist Information Board showed the 1851 Meeting site as the ‘Protest Meeting‘ . The map was prepared by Geoff Hocking, using background material provided by researcher Barbara James. In 1999 the FOMAD book ‘Exploring the Mount Alexander Diggings similarly identified the location of the Meeting as ‘near today’s junction of the Pyrenees Highway and Golden Point Rd a couple of kilometres east of Chewton Town Hall.

As interest in the history of the 1851 Meeting grew so too did vigorous debate about the location of the site in the contemporary landscape. Interested locals suggested various potential sites – all in the general area indicated by the earlier maps.

In December 2003 the Castlemaine Mail (19/12/2003, p1 & 3) reported that locals gathered to celebrate the anniversary of the Meeting at “the junction of Pyrenees Highway and Golden Point Rd Just a ‘stone’s throw’ from where the diggers met on that hot and dusty day at a shepherd’s hut in 1851.”

A little later, in June 2004 the Castlemaine Mail reported that the 1851 Meeting site had been ‘pinpointed‘ at Chewton. It reported that Chewton resident, Glenn Braybrook, by comparing an 1853 mining lease map from the Barbara James collection and Richard Tulloch’s 1851 drawing of the Meeting, was able to pinpoint the location of the old bark Shepherd’s Hut, which was verified by Heritage Victoria advisor, archaeologist David Bannear and Clive Willman from Geological Survey. It reported that David and Clive using an overlay technique with more recent maps to pinpoint the position of the Hut identified by Glenn, concluded that it ‘was in fact the site of the Monster Meeting’. The people gathered to celebrate the site included eminent historian Professor Weston Bate, who stressed that ‘the importance of this site could not be overestimated’, and David Bannear who claimed the Monster Meeting as ‘the birthplace of Australian democracy‘.

In 2008 local resident Ken McKimmie identified the site of the shepherd’s hut and the 1851 Meeting by focussing on a detailed analysis of the geography of the area. He used sketches and paintings done at the time of the Meeting and compared them with images from the modern day. His method of analysis and conclusions about the Monster Meeting site are explained on pages 62-65 of his 2011 book, Chewton Then and Now.

Then in 2017 Ken located a very high resolution copy of a photo taken by Richard Daintree in 1858 that depicts the general area of the Monster Meeting site. While the location from which the photo was executed was always known, he was able for the first time to identify a known reference point in the photo, namely Thomas Meredith’s British and American Hotel, once located on the corner of Main Rd and Golden Point Rd. It was therefore possible to narrow down the site of the 1851 Meeting and locate a building that is likely to be the old shepherd’s hut. This lead to the following article ‘Is this the Monster Meeting site?’ that appeared in the Chewton Chat in 2017.

The continuing debate about the Meeting location grew more heated, leading to an article in the Chewton Chat in January 2016 by Editor, John Ellis, that sought to return some sense to it all – An historical question that turned hysterical.

And then the Victorian Heritage Council took an interest and initiated an investigation following an application from Chewton Domain Society member, John Ellis. The Victorian Heritage Council’s comprehensive investigation to determine the location and extent of the site was done by local archaeologist David Bannear and included detailed consideration of all available historical and contemporary evidence, including written and verbal submissions from four interested local residents. As a result of this investigation the site of the Diggers’ 1851 Monster Meeting was listed in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR2368) on 13 July 2017.

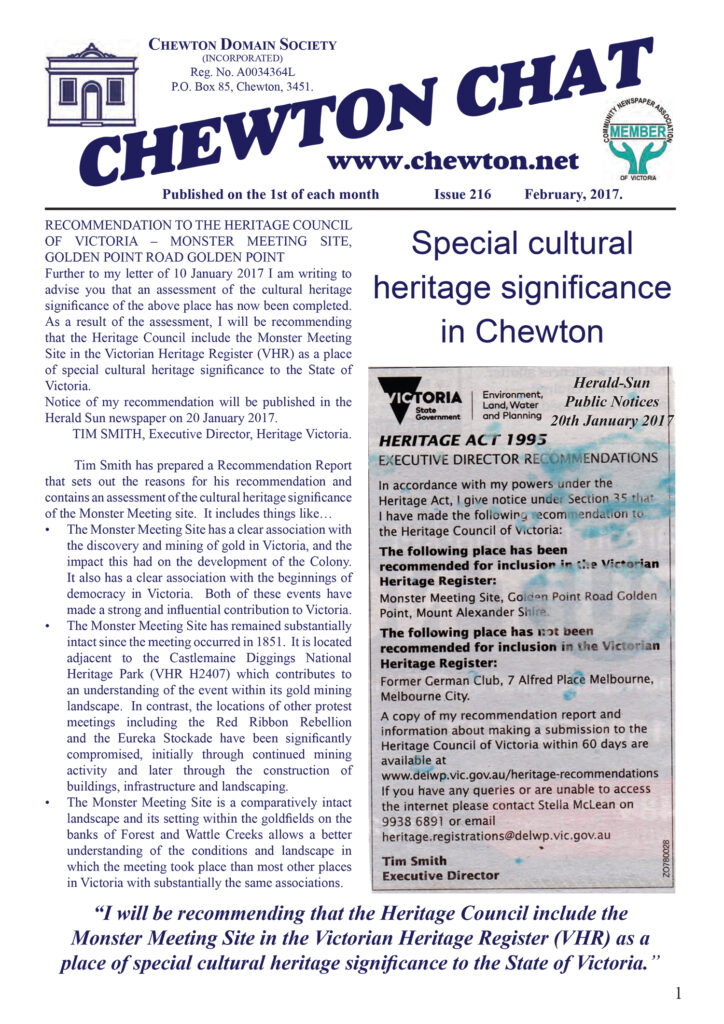

A letter from Tim Smith, Executive Director of Heritage Victoria, explaining the reasons for the Council’s recommendation, was reprinted in the February 2017 Chewton Chat.

It is difficult to judge the precise parameters of the 1851 Meeting area because the thousands of people present would have spread out over quite a large area. However, the Heritage Council investigation identified an area extensive enough to encompass such a large crowd for listing of the site in the Victorian Heritage Register. The identified site included some privately owned land on Golden Point Rd adjacent to the Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park. It was purchased by the Victorian government at the time of the listing and was integrated into the site already included in the Castlemaine Diggings National Heritage Park, ensuring that the whole of the 1851 Monster Meeting site remains as public land.

A few people still dispute the accuracy of the findings of the Victorian Heritage Council’s investigation and continue to suggest various alternative sites nearby.

The Heritage Council report can be read here.