DIGGERS’ 1851 MONSTER MEETING

Most people know that the Eureka Stockade at Ballarat in December 1854 played a major part in the early development of Australian democracy – it’s an Australian legend. Not so many know that Eureka had its beginnings three years earlier at the Diggers’ 1851 Monster Meeting at Forest Creek on the Mount Alexander goldfields. There 15,000 diggers stood united and successfully defied Governor La Trobe’s attempt to double the already exorbitant cost of their gold licence. This 1851 Meeting ignited a protest movement that spread across the Victorian goldfields. The Eureka uprising was the final act in three years of organised protests demanding an end to licences and more democratic rights. It finally ended the old order on the goldfields.

READ THE STORIES OF THE MONSTER MEETING

The Rush Begins

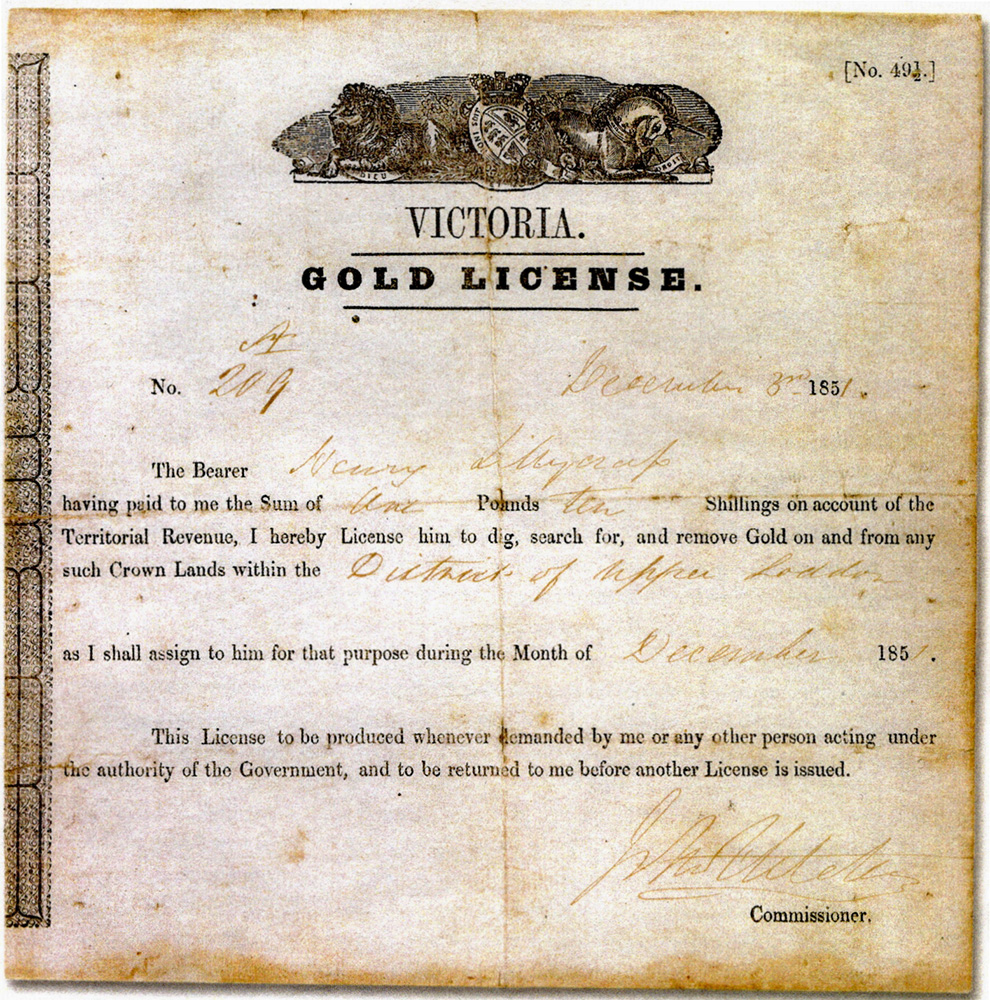

In August 1851, six weeks after the Colony of Victoria was proclaimed the gold rush began. Following reports that gold had been found at Clunes and Buninyong and then at Ballarat, the Victorian Lieutenant Governor Charles La Trobe, issued new regulations. Persons searching for gold in Victoria had to obtain a gold licence costing thirty shillings per month and also show proof that they were not “a person improperly absent from hired service”.

The gold licence system had a two-fold purpose. First, it was to raise the money needed to fund the cost of goldfields administration and infrastructure. Second, it was to stop the rush, control the labour force and get people back to their jobs in workshops and farms in time for the shearing and harvest. But the money raised was not enough because many of the gold diggers were either not able or not willing to pay 30 shillings a month for a licence. Evidence from various official sources, plus much anecdotal evidence, indicates that as many as 50 per cent evaded the licence fee at some time in their mining lives. Most importantly, introduction of the gold licences did not stop the rush.

Governor La Trobe had a deep mistrust of social disorder and democracy and he could see that his plans for the gradual development of the new colony along “sound religious and moral traditions” would be swept away by the social turmoil of the gold rush. The rush had to be stopped and the gold diggers forced back to the farms and the abandoned shops and workplaces of Melbourne and Geelong. But the diggers had other ideas. Although they came from all walks of life, most were ordinary working people and for them the gold rush was an opportunity to find riches and build a better life than they could get toiling in the workplaces of their masters, where they were bound by the Masters and Servants Act designed to control workers and repress trade unions. They could not vote and they had little in the way of civil rights but they were not deterred by La Trobe’s attempts to stop them joining the rush that was already threatening his plans for the new colony. His plans did not include more civil rights and the vote for working people – he was no democrat.

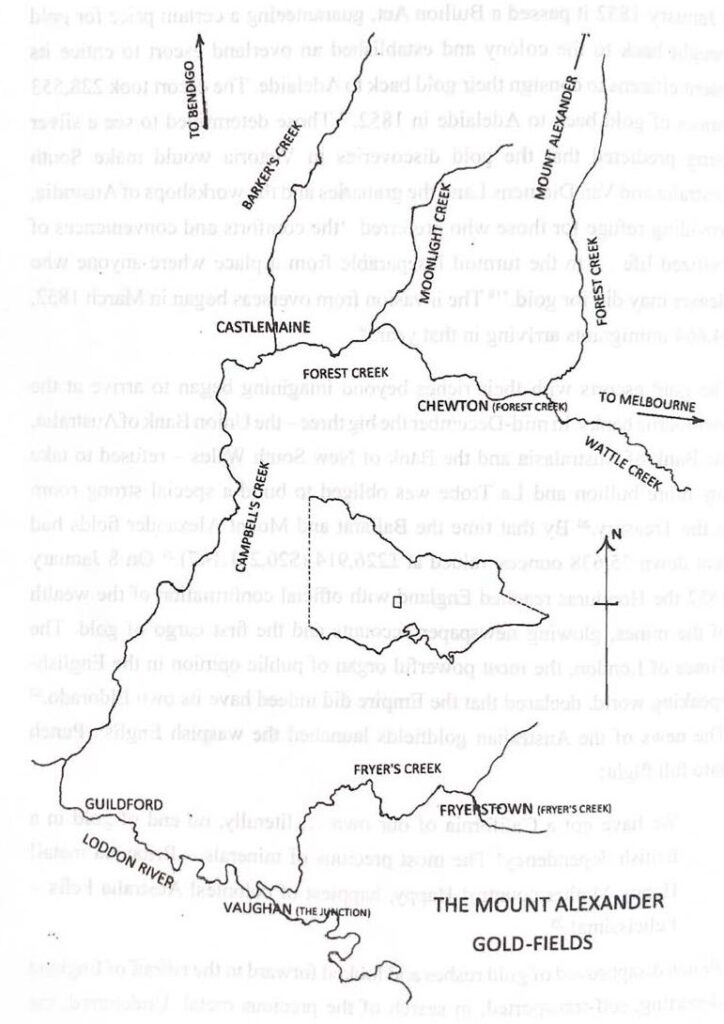

In September 1851 the Melbourne Argus newspaper published a letter from miner John Worley describing where gold could be found at Mount Alexander. Within weeks thousands tramped along the Mount Alexander Rd (later to become the Calder Highway) to look for that gold. By December there were 25,000 panning and digging at Forest Creek, the richest shallow alluvial gold field ever found. Some were making a fortune, some were making wages (more than in the workplaces they left behind) but some found little gold and faced destitution. But whether they found gold or not La Trobe and his government expected them to pay 30 shillings a month for a gold licence or face fines and jail.

By December it was clear that the gold rush could not be stopped and La Trobe was faced with increasing government costs to administer the goldfields and a growing labour crisis as people abandoned their jobs and homes to join the rush. In desperation he made a grave error of judgement. He announced that the already exorbitant cost of the monthly licence would be doubled to three pounds (sixty shillings) on the first of January. He believed wrongly that this would both stop the rush and raise more money for his cash strapped government. But it did neither.

There was an immediate response to La Trobe’s announcement. Across the goldfields groups of diggers gathered in their camps to express their opposition. The Argus, reporting on a campfire gathering of 50 miners at Buninyong, described them as “men strong in their sense of right, lifting up a protest against an impending wrong, and protesting against the Government.” It concluded: “It is a solemn protest of labour against oppression – an outburst of light, reason and right against the infliction of an effete, objectionable royal claim brought forward to crush a new branch of industry, whose birth was heralded by large rewards, and whose death will be laid at the door of the Government”.

The Diggers’ Monster Meeting

At Forest Creek copies of a Manifesto (printed on an illegal printing press) were posted along the creek. It conceded that gold was the property of the Crown and those who mined it should pay a fair percentage of what they gained but called for a more equitable tax than the gold licence system provided. But, as historian Marjorie Theobald notes, the Manifesto “spoke the language of class warfare and that was anathema to the British ruling class”.

Argus, Monday 8 September 1851. p2.

NEW GOLD FIELD – We have received the following letter announcing the discovery of a new gold field at Western Port.

DEAR SIR, I wish you to publish these few lines in your valuable paper, that the public may know that there is gold found in these ranges, about four miles from Dr Barker’s home station, and about a mile from the Melbourne road; at the southernmost point of Mt Alexander, where three men and myself are working. I do this to prevent parties from getting us into trouble, as we have been threatened to have the constable fetched for being on the ground. If you will have the kindness to insert this in your paper, that we are prepared to pay anything that is just when the Commissioner in the name of the party comes.

John Worley, Mt Alexander Ranges, Sept 1st 1851

On Monday 8 December another notice appeared along the creek calling diggers to attend a preliminary meeting at 7.00pm that night near the Post Office, to consider the government proposal. John Howard, local Argus reporter on the spot, reported that some 3,000 attended. After the leaders of the meeting (and authors of the Manifesto) John Plaistowe, Edward Potts and Henry Lineham addressed the meeting, it was agreed that a committee be appointed to call on local Gold Commissioner Frederick Powlett and ask him to “call a general meeting of the diggers from all parts of Mt Alexander, for the purpose of taking into consideration the Proclamation of His Excellency the Lieutenant Governor relative to increasing the licence fee from thirty shillings per month to three pounds and for other business connected with the diggings.” The committee was appointed and called on Commissioner Powlett the following morning, requesting that he call such a meeting on the following Monday December 15. But Powlett declined their request and left for Melbourne to meet with Governor La Trobe and warn him of their plans to call an even larger mass meeting of diggers on the Mount Alexander goldfield the following week.

Undaunted, the Committee went ahead and called the meeting (later known as the Monster Meeting) for 4.00pm Monday 15 December at the old bark shepherd’s hut by Forest Creek. To advertise it, 1,000 handbills were printed (again illegally) and posted throughout the field and an advertisement was placed in the Argus of Friday 12 December calling on miners to come to the meeting. Given that the Friday Argus would not get to Forest Creek before the Meeting on Monday, the advertisement would not affect the numbers attending the meeting but it would inform the people of Melbourne and Geelong, including La Trobe and his government, of their intention to organise a mass meeting of thousands of diggers to voice their opposition to the proposed increase. Meanwhile opposition was growing across Victoria with critical articles and editorials in Melbourne’s major newspapers, the Argus and the Melbourne Morning Herald, and reports of opposition from all sections of society.

In response to this growing opposition and fearing major civil unrest on the goldfields, La Trobe backed down. On Saturday 13 December the Colonial Secretary’s Office prepared a formal written announcement that the proposal to double the licence fee would be rescinded. This official notice was published in the Victorian Government Gazette on 17 December, but the news was printed beforehand in the Argus on Monday 15 December, which did not reach Forest Creek until days later. But the diggers at Forest Creek did not hear about the recission before their meeting went ahead as planned.

Colonial Secretary’s Office, Melbourne. Dec. 13. 1851

Measures being now under the consideration of Government, which have for their object the substitution as soon as circumstances permit of other Regulations in lieu of those now in force, based upon the principle of a royalty leviable upon the amount actually raised, under which Gold may be lawfully removed from its natural place of deposit. His Excellency the Lieutenant Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, hereby causes it to be notified, that no alteration will for the present be made in the amount of the License Fee as levied under the Government Notice of the 18th August 1851; and that the Government Notice of the 1st inst., is hereby rescinded. By His Excellency’s Command, W. Lonsdale.

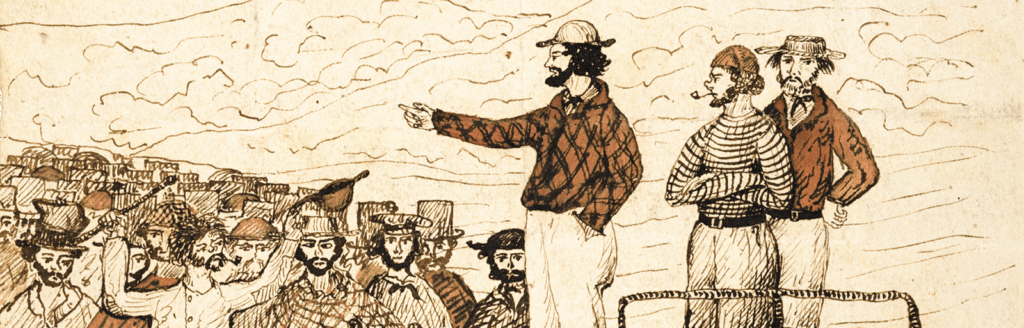

On the afternoon of Monday 15 December, all over the Mount Alexander goldfield, diggers downed tools and, to the music of Hore’s Sax-Horn band, 15,000 gathered at the old bark shepherd’s hut to hear and cheer the speakers: J F Mann, Robert Booley, Henry Lineham, Dr Valentine Webb Richmond, Edward Potts, John Plaistowe, Captain John Harrison and E Hudson. And once again John Howard recorded the speeches and resolutions for publication in the Argus a few days later.

Read the full text of speeches: SPEECHES FROM THE DRAY – WHAT THEY SAID

The meeting began at 4.00pm with a dray as a platform for the speakers and a new flag flying. J F Mann, the Chairman, called first on Edward Potts. He condemned the licence fee as an unlawful tax and reminded the Meeting that Britain’s American colonies had been lost because of such a tax. He then proposed the first resolution that was carried by the Meeting:

That this meeting deprecates as unjust, illegal and impolitic, the attempt to increase the licence fee from thirty shillings to 3 pounds.

Potts was followed by Henry Lineham who proposed a more controversial resolution, which was also carried by the Meeting:

That this meeting while deprecating the use of physical force, and pledging itself not to resort to it except in case of self defence; at the same time pledges itself to relieve or release any or all diggers that on account of non-payment of three pound licence may be fined or confined by Government orders or Government agents, should Government temerity proceed to such illegal lengths.

This proposal was tested some time later at the McIvor (Heathcote) diggings in August 1853, when a crowd of diggers successfully demanded the release of prisoners who were arrested for not having a licence.

Captain John Harrison spoke to great applause. He had ridden from the newly opened field at Bendigo where he had organised a meeting of 200 in support of the Forest Creek diggers the previous week. He urged the formation of an association to watch over the diggers’ interests and proposed the following resolution, which was also carried:

That the miners at each diggings appoint Committees to watch over their interests, and that a Central Committee be formed by a Delegate from the Committee of each of the diggings, such delegates to be paid for their services, and report proceedings to a General Meeting of the miners, to be held the first Monday of each month.

The next speaker was Dr Valentine Webb Richmond, a British doctor and knowledgeable geologist who had organised the earlier Bendigo meeting with Captain Harrison. He proposed the following resolution, also carried by the Meeting.

That Delegates be named from this Meeting to confer with the Government and arrange an equitable system of working the goldfields.

Captain Harrison, Dr Webb Richmond and John Plaistowe were appointed as the Delegates to confer with the government about this proposal.

The next speaker was Robert Booley, a Wesleyan lay preacher and pioneer of the British trade union and Chartist movements, who had migrated to Geelong in 1848 where he was a pioneer of the eight-hour day movement. He used the issue of the licence to speak about the need for justice, for a just Government and the rights of working class people to full democratic rights and a better life. He urged those at the Meeting to act to support these principles and each other.

“There are few people who properly understand what a Government is, or what it ought to be. It should be the chosen servants of a free people, and to be just they ought to be a right-minded people. …… What ought to be the standard of man? Justice. Why do we cry out against Government? Because they do not do justice.”

The final speaker, Mr E Hudson, acknowledged the “quiet orderly manner” of the meeting and urged everyone to “assert your rights, be steady to your purpose but keep your powder dry”.

The Meeting ended with cheers for the diggers and the Argus and people dispersed back to their tents and campfires to the music of Hore’s Sax-Horn Band. Argus reporter, John Howard ended his report of the meeting with the following words:

“During Captain Harrison’s address, there could not have been less than 14,000 persons on the ground, not a cradle was seen to be working. The men appear to have risen en masse, at the sound of the band, and retired in the same order.”

Read the full account of WHO WAS THERE.

Richmond, Harrison and Plaistowe later obtained a meeting with Colonial Secretary William Lonsdale, but it achieved nothing. Their written submission, Memorandum of Propositions for regulating the goldfields, was dismissed without any further consideration by La Trobe. But a few days later they addressed a large meeting on Melbourne’s Flagstaff Hill and announced that the Victoria United Gold Miners’ Association had been formed to melt and assay gold on the diggings and a miners’ bank was under consideration. The Association was short-lived and the bank did not eventuate but, as historian Marjorie Theobald points out, the Flagstaff Hill meeting importantly “demonstrated the potential to unite the men on the fields with their supporters in Melbourne and set a precedent for future action on other fields.” For La Trobe and his advisors these implications were clear and unwelcome: agitation on the goldfields could impact official Melbourne and its banks and jails.

The Diggers’ movement at Forest Creek largely dissipated within a few weeks but, as Marjorie Theobald notes, their actions set a pattern of popular protest against the administration of the goldfields orchestrated by leaders who were better educated, more articulate, more politically aware, and willing to live outside the search for gold. Their leaders shaped the Diggers’ concern about the licence system into a broader challenge to the established order. They made the link between the inchoate discontent of the ordinary miners and the broader political context of the times.

The Diggers’ success in stopping the licence fee increase did not end conflict over the licence system, but it had a transforming impact. Their peaceful mass declaration of civil disobedience ignited the protest movement that spread across the Victorian goldfields demanding greater civil rights and an end to the gold licence. And it created a political force of men and women who understood that their strength lay in unity – the Diggers – a connecting thread through the growing protest movement of the next three years.

And in response La Trobe came to the conclusion that greater military force was needed to control the miners. A view Marjorie Theobald describes as “a decision looking backward to Australia’s past as a convict society under a military regime, rather than forward to a community of free and self-governing people. …. On the goldfields the presence of the military cast a pall over relationships between the camp and the miners, an everyday reminder that they were British citizens without rights, suffering under a military regime which controlled every aspect of their lives. A Gold Commission founded on the premise of military despotism inevitably set itself at odds with those it was called into existence to serve.”

And this was the dual legacy of the 1851 Diggers’ Monster Meeting at Forest Creek. It simultaneously ignited a protest movement across Victoria and strengthened the government’s determination to control the goldfields with military force. This inevitably created confrontations and unrest across the goldfields over the next three years and set the scene for the two major confrontations that transformed Victoria. In mid-1853 the Diggers’ Red Ribbon Movement in Bendigo forced La Trobe’s government to reduce the licence fee and draft the long delayed Victorian constitution which went to London for royal assent in March 1854, eight months before the Eureka Stockade was raised. (It was finally proclaimed by Governor Hotham in 1855.) The confrontation at the Eureka Stockade in December 1854 finally ended the old order on the goldfields.

In considering the legacy of the Diggers’ 1851 Monster Meeting, Marjorie Theobald asks: “When the first Victorian Parliament sat in November 1856 did anyone present on that momentous day remember the men and women who assembled around the shepherd’s hut at Forest Creek in December 1851? They are remembered now by the people of Chewton who meet each year on the same ground and they are honoured for the stand they took and the example they set to oppressed people everywhere.

This paper tells the story of how the men and women who came to the goldfields in the

1850s transformed the new colony of Victoria and started and drove the development of

parliamentary democracy. Download the paper here.

In 2014 the Chewton Domain Society published The Monster Meeting Book , written by Jan ‘Yarn’ Wositzky, with financial assistance from the Ballarat Reform League, the Australian government ‘Your Community Heritage Program’, Parks Victoria, Mt Alexander Shire and local businesses and community organisations.

Jan explains how the book came into being:

The principal matters I was trying to comprehend were about what was going on in Melbourne: how was La Trobe reacting to the goldrush; why was he making so many poor decisions; What power did the squattocracy have over government decisions; what were the middle class interests in favour of the diggers; and what was the wider Australian context of Chartism and the movement for democracy across the world. But very soon the main question became: What is the legacy of the Monster Meeting? What role did it play in the train of events that lead to Eureka and in the development of our Australian democracy? In this book, some of these questions are partly answered and some are left hanging. … There is still much more research and work to do to write this into a definitive history of the events leading up to the Monster Meeting and its aftermath, but this will now have to wait till another day.

However, notwithstanding this limitation, this book gives a reasonably clear narrative of events between 1 July 1851 and early 1852, and a sketch of the period through to the Eureka tragedy on 3 December 1854. I hope that this will help the reader come to understand that Eureka began on the Forest Creek diggings with the Monster Meeting of 1851.

Charles Joseph La Trobe was appointed Superintendant of the Port Phillip district of NSW in 1839 and subsequently became the first Lieutenant Governor of the new colony of Victoria in 1851 until his departure in 1854. For details of his life go to the Australian Dictionary of Biography (http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/la-trobe-charles-joseph-2334)

Overall there is general agreement (albeit with varying levels of criticism) about La Trobe among those who study the early years of Victoria. That he governed at a difficult time with little support is generally accepted and that he made positive contributions to the cultural life of the new colony. His generally acknowledged failures and the inadequacies of his administration, particularly in managing the gold rush, are variously ascribed to the difficult and chaotic times, the opposition of squatters and members of the Legislative Council, the hostility of the media, his personal characteristics and his distrust of democracy and lack of administrative skills. Indicative is the faint praise given in his citation for the Order of the Bath in 1858, reading:

With regard to his administration of the Government of Victoria, if it was not marked by any very brilliant results, he carried the colony through unprecedented difficulties with safety and laid the way for future success.

Charles La Trobe (1801 – 1875) was born in London into a family of the evangelical Moravian (Christian) faith. He was a cultured gentleman of his time: linguist, author and traveller in Europe and North America who, in keeping with his cosmopolitan outlook, married a Swiss national, Sophie de Montmollin, also from a wealthy Moravian family. La Trobe lacked the usual background for a colonial governor. He had no army or naval training and little administrative experience – he was a cultured gentleman rather than an intellectual or executive. From the time of his appointment in 1839, he was an active supporter of the religious, cultural and educational institutions of early Melbourne including the Botanic Gardens, Mechanics’ Institute, Royal Melbourne Hospital, Benevolent Asylum, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and University of Melbourne.

Historian Marjorie Theobald questions whether this background rendered him more or less fit for his 1839 appointment as Superintendent of the Port Phillip district. She notes that as Superintendant he was happy to play second fiddle to the Governors in New South Wales but his tendency to sit on the fence made him enemies. The squatters accused him of failing to procure their security of tenure in a timely manner, he did not press for the separation of Port Phillip from New South Wales; he equivocated on the matter of the transportation of convicts; and the Melbourne Town Council accused him of a number of vague and trivial sins and the splenetic editor of the Argus, William Kerr, set out to destroy him.

Then in 1851, soon after the Port Phillip district was granted independence as the colony of Victoria, events overtook the new Governor. The gold rushes hit the new colony with the force of a tsunami and overturned his plans for the ‘planned gradual development of the colony along sound religious and moral traditions’. The unstable conditions that were created by the gold rush lasted for the rest of his time as Governor. Historian Dianne Reilly, La Trobe’s biographer, notes that ‘for a man like La Trobe, with his profound mistrust of social disorder and democracy such social instability was intractable and baffling’.

La Trobe’s first response to the gold rushes was statesmanlike. He predicted that Victoria would benefit greatly from its new-found wealth, and he warned his superiors in Westminster that no measures could prevent men from pursuing this most democratic form of mining. But personally he had grave misgivings about what impact the discovery of gold would have on colonial society and in his private correspondence in June 1852 he lamented, “I would to God that not a grain had ever been found”. As historian Marjorie Theobald comments: “In his thirty-three tumultuous months in charge of the goldfields, La Trobe could never make up his mind whether he was presiding over a disaster of Californian proportions or the birth of a new and glorious era which would elevate the colony to pre-eminence in the British Empire”.

Reilly notes, ‘he was made nervous by the turmoil generated by the discovery’ and he was left with ‘a sense of the gold rushes as dangerous events with unpredictable outcomes’. With the exodus of civil servants to the goldfields he was left with few advisors and little support, a situation that ‘brought out two opposing traits in La Trobe’s character: timidity and authoritarianism. He was afraid of making decisions which might be wrong in the eyes of Governor FitzRoy in Sydney and the Colonial Office in London, and he believed in the authority with which he had been invested. The result was that, with no support, he lost confidence in ever being able to resolve the situation and gave up as the decision-maker’.

Reilly further notes that La Trobe had never found administration of the colony to be easy due to his personal characteristics but his management of the goldfields was the weakest part of his administration. He had little choice but to put in place some form of governance of the gold fields and some form of taxation for extracting gold from Her Majesty’s Crown lands. However, his choice of the monthly licence fee and the military-style Commissioner’s camps alienated men who saw themselves as British citizens with inalienable rights. When the miners organised to protest against the licence fee and the bully boy tactics employed to collect it, beginning at the Forest Creek Monster Meeting in December 1851, La Trobe panicked. He wrote to Westminster in terms which implied that sedition and republicanism were a real danger to Her Majesty’s Empire in the southern seas.

When the Bendigo miners, fresh from the Red Ribbon Rebellion, met with La Trobe in August 1853 to present their Bendigo Petition, he similarly responded defensively, refusing their principal request for reduction of licence fees and asserting himself as the authority figure. While he could see that the miners had real problems with the licensing system, he was fearful of anarchy on the goldfields and he still needed an alternative way to raise the necessary revenue to keep the colony functioning. The meeting was not a success. Reilly comments that ‘had La Trobe been able to act differently perhaps the tragedy of Eureka would have been averted. … He could not put himself in the miners’ shoes’. He could not feel for them in their struggle for basic acknowledgement and rights.’

La Trobe had little sympathy with the new society which was emerging in the Australian colonies. By 1853 his ailing wife and children had returned home to Switzerland and he concluded that his period of effectiveness as Governor of the Colony had come to an end. He tendered his resignation but his departure was delayed until early 1854 after he was replaced by Charles Hotham.

NB. The information and some of the wording of this note on Charles La Trobe are taken from the work of historians Dianne Reilly and Marjorie Theobald with thanks for their insight and scholarship.

One source of the term ‘Monster Meeting’ comes from Ireland in the 1840s – the decade before the Diggers’ Monster Meeting in 1851 – when Irish patriot Daniel O’Connell led a movement to repeal the 1800 Act of Union, a British law abolishing the Irish Parliament and making Ireland a part of the United Kingdom.

The campaign began during the general election campaign of 1841, which brought to power O’Connell’s bitter adversary, the British Tory Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel. The peasantry of Ireland contributed their pennies and farthings to a fighting fund, known as the ‘Repeal Rent’, and Daniel O’Connell addressed a series of ‘Monster Meetings’ across the country, some attended by gatherings of 300,000 people.

The greatest Irish monster meeting was on the Hill of Tara on 15 August 1843, attended by at least 750,000 people. To use an adjective that’s much degraded these days, the spectacle must have been awesome. For three days in advance, from a wide radius by carriage, horse and on foot, people thronged to the famed hill. The fields for miles around were filled with vehicles. Bands, ceremonial floats and thousands of banners added colour as the occasion became as much a festival as a political rally. Priests and laymen made sure that there was no disorder, no shillelaghs and no strong drink. Altars were erected on the various mounds around the hill and masses were celebrated on the morning of the rally. Two bishops and 35 priests were present as, soon after midday, O’Connell’s carriage slowly made its way up to the top of the hill.

As he spoke, O’Connell’s words were relayed down the hill by officials assigned to that task. The vast audience shouted, laughed, groaned and exulted at appropriate moments during O’Connell’s stentorian oratory – including those who were too far away to hear what was being said. In all there were over 40 Monster Meetings across Ireland in 1843, held at important historic and Celtic sites. Daniel O’Connell traveled up to 5,000 miles by coach to address 31 of these meetings himself.

In comparison the Forest Creek Monster Meeting was attended by an estimated 15,000 people. Barring a monumental gathering of Aboriginal Australians that we don’t know about, it was to that time the biggest gathering of people on the Australian continent. We’ve often wondered how the 15,000 there actually knew what the speakers said. The explanation from Tara of people relaying the speech to the back of the crowd is the most likely. However some may never have heard a word and, as Robyn Annear points out in her interview on this website, many wouldn’t have finally comprehended what was said till several days after the meeting when they read the Argus newspaper.

The Forest Creek gold rush was a ‘domestic’ gold rush, attended by people already living in Australia. The Forest Creek Monster Meeting was not attended by a coterie of Irish republicans with experience of the struggles in Ireland. They came later and were prominent at Eureka in Ballarat in 1854. Also, the men who spoke at the Forest Creek Monster Meeting identified themselves as proud ‘Britons’. But the population in Australia would certainly have read of the Monster Meetings and who could not be inspired by the gathering at Tara.

LISTEN TO THE STORIES

These six interviews about the Monster Meeting and the related history of the 1850s Victorian gold rush, conducted by Jan ‘Yarn’ Wositzky, are interesting, informative, insightful, and full of wonderful storytelling, sharp historical insight, differing perspectives and new information about the political movement for democracy that was a hallmark of the 1850’s Victorian gold rushes.

The interviews are easy to follow, provide a fast track into understanding this significant event in Australian history and reveal events that former accounts of the gold rush have overlooked. The principal thesis behind them is that the Diggers’ Monster Meeting on 15 December 1851 at Forest Creek united the individual gold seekers into a political force that became the Diggers and subsequent events at the Eureka Stockade at Ballarat in 1854 had their beginnings at the Monster Meeting in 1851. The 1851 Monster Meeting was a first step on the path to democracy in Australia.

The order of interviews is structured to progress from an introduction and overview of the Monster Meeting and the gold rush through to in-depth political and social analysis and discussion of the machinations of the Victorian Legislative Council and Governor Charles La Trobe, global issues of democracy, then and now, the relationship of the Monster Meeting to the Eureka Stockade at Ballarat in 1854 and the legacy for us today, including issues such as the gold rush landscape and how Indigenous people fared in the gold rush.

You can also listen to parts of these interviews on disk 2 of the MONSTER MEETING CD where the story is told by them and others in words and music.

1. ROBYN ANNEAR: (69 minutes)

Robyn Annear is a writer and historian and gifted storyteller who paints a vivid and humorous picture of the goldfields, the characters, the political issues, the meeting itself and the meaning of it all. Robyn’s books include Bearbrass; Imagining early Melbourne (Mandarin 1995), Nothing But Gold: The Diggers of 1852 (Text 1999) and A City Lost and Found: Whelan the Wrecker’s Melbourne (Black Inc. 2005). Robyn also hosts a podcast, Nothing on TV, telling stories from old Australian newspapers. For more wit and information go to robynannear.com.

2. DOUG RALPH (35 minutes)

Castlemaine born and bred, Doug Ralph was a Castlemaine living treasure, well-known environmentalist, activist, and local historian who sadly died in February 2015. His knowledge of the local landscape was unparalleled, and his Sunday morning bush walks were a delight for many. In this interview Doug tells how the Monster Meeting was revived in 1995, contextualises the gold rush within a longer history of the land and Indigenous people, and talks about the legacy of the Diggers’ Monster Meeting. Doug was the instigator of the present day commemorations of the Monster Meeting.

3. GEOFF HOCKING (17 minutes)

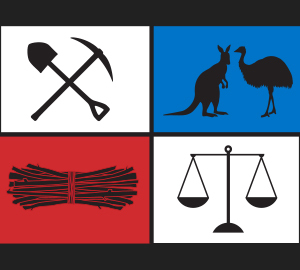

Geoff Hocking is a Castlemaine based author, publisher, historian and artist. In the spirit of the Monster Meeting, Geoff provides a dissenting interpretation of the current Monster Meeting flag and talks of the history of Chartist monster meetings in Great Britain, and of the values we inherit from the Diggers’ 1851 Monster Meeting. His books relating to gold rush history include Early Castlemaine: A Glance at the Stirring Fifties (New Chum Press, 1998), The Red Ribbon Rebellion! Decade of Dissent , (New Chum Press 2001), Castlemaine: From Camp to City (New Chum Press, 2007), Gold. Off to The Diggings (New Chum Press, 2010), Under the Southern Cross (Five Mile Press, 2012) and The Rebel Chorus (New Chum Press, 2019).

4. PROF. MARJORIE THEOBOLD (54 minutes)

Marjorie Theobald (née Madigan) takes us deeper into the political machinations in early Victoria, the Monster Meeting and the gold license, with a keen and incisive eye for the character of Governor La Trobe, the squattocracy, the diggers, and the consequences of the Monster Meeting. Marjorie is descended from several families who came to the gold rushes and stayed to make a home. She inherited a love of goldfields history from her father who was still sluicing for gold in the 1930s and 40s and has written a history of her family and a history of the first 10 years of the Mount Alexander gold rush (Mount Alexander Mountain of Gold 1851-1861. The gold rush generation and the new society) and a history of the first 10 years of the establishment and development of the town of Castlemaine (Accidental Town).

Marjorie left Castlemaine in 1959 for the University of Melbourne, graduated in Arts and Diploma of Education, became a secondary school teacher, completed her Ph.D. at Monash University, and then returned to University of Melbourne as a historian in 1988 and published extensively in the history of education. In 2002 Marjorie and her husband John returned to Castlemaine where she shifted her focus to the history of the goldfields and the town. Her latest book, The Accidental Town. Castlemaine 1851 -1861 (Australian Scholarly Publishing 2020) recreates the early years of the gold rush when Castlemaine was transitioning from a mining camp to a settled town.

5. PROF. WESTON BATE OAM (55 minutes)

With this great historian we go further into the social politics of the gold rush and the Monster Meeting, viewing the events and times as one of social revolution in concert with the 1840s revolutions in Europe, containing elements of republicanism and small-l liberalism, powered by the union of capital and labour and the liberation provided to the ordinary worker by the “democratic mineral” – gold.

Weston Bate, who died in October 2017, was a social historian and author of many books, including Lucky City: the first generation at Ballarat, 1851–1901 (Melbourne University Press, 2003), Victorian Gold Rushes (Sovereign Hill Museums Association, 1999), Having a Go: Bill Boyd’s Mallee (Museum of Victoria, 1989, with Bill Boyd) and Essential but Unplanned: the story of Melbourne’s Lanes (State Library of Victoria, 1994). Weston was Head of Australian History at Melbourne University and Professor of Australian Studies at Deakin University, served in the Australian Air Force during World War Two, and began his working life as a primary school teacher.

6. DAVID BANNEAR (28 minutes)

David provides a philosophical and emotional overview of the land of the gold rush: how the 1851 Meeting shaped the gold seekers into becoming the Diggers, which led to Eureka, and spawned the skilled communities that continue to thrive in the gold fields country – towns that are welcoming places to outsiders, where the story is still there in the country for everyone to become part of and to inherit.

David’s speciality is Victorian mining heritage – chiefly gold mining, but also copper mining in the South Australian context – as well as historic forestry and infrastructure.

He recently retired from working for Heritage Victoria as an archaeologist. He worked and liaised with a wide range of land owners/managers, including local and State government authorities, dealing with issues of historic heritage.

Interview Credits

Written & co-produced by Jan ‘Yarn’ Wositzky

Filmed, edited & co-produced by Davide Michielin

Lighting & sound: Denise Martin

Executive producer for Chewton Domain Society: John Ellis

Funded by Ballarat Reform League with assistance from the Vera Moore Foundation & the Australian Government’s Your Community Heritage Program (Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities).

In Disk 2 of the Monster Meeting CD Jan ‘Yarn’ Wositzky and others tell the story of the 1851 gold rush and its legacy in words and music.

Part One: The Monster Meeting Today. The modern Monster Meeting celebrations begin in 1995 with protests against the Kennett Victorian Government’s amalgamation of local councils, and the replacement of locally elected councillors with Government appointed Commissioners. It was Government Commissioners after all, who administered the conflicted gold fields.

Part Two: The 1851 Gold Rush. The rolling hills of Djadjawurrung country become a squatter’s paradise – Australia Felix. In turn the 1851 Mt Alexander/Forest Creek gold rush turns the squatters’ world upside down. To deter lowly paid workers leaving their jobs, Governor La Trobe institutes a gold licence of thirty shillings a month. The gold licence fails, and 25,000 diggers are camped on Forest Creek. La Trobe moves to double the fee.

Part Three: The Monster Meeting 1851.The Mt Alexander/Forest Creek diggers read in the Argus of La Trobe’s plan to double the fee and two meetings are called. At the second, the Monster Meeting of 15 December 1851, the speakers call for justice and their rights. The diggers vow not to pay the doubled fee.

Part Four: Bendigo and Ballarat. Governor La Trobe backs down. The gold licence stays at thirty shillings. But La Trobe brings in as system of corrupt policing to administer the diggings. The conflict between the diggers and the government moves to a new rush at Bendigo, with the Red Ribbon Agitation of 1853, then explodes into bloodshed at the Eureka Stockade Ballarat on 3 December 1854.

Part Five: The Monster Meeting Legacy. Historians and locals look back: the Monster Meeting set a path to democracy in Australia, and as the first mass protest against an Australian government, the Monster Meeting remains an inspiration for us all to stand up for our rights.

ON THE INTERNET

This 2.40 minute video tells the story of the Monster Meeting against some great graphics. It can be viewed here.

The electronic encyclopedia, egold, tells the story of gold in Australia through images, stories and interactive multi-media. It connects individual stories to wider historical themes including building the Australian nation and democratic change during the gold rushes. It locates the Monster Meeting in the wider stories about democracy and protest and development of law and order. Read more at www.egold.net.au (go to 1851 Monster Meeting @ Democracy & Protest and Law and Order)

Eurekapedia Wiki includes information about events before, during and after the Eureka Stockade battle of 3 December 1854. It is hosted by the Ballarat Reform League and can be accessed at www.eurekapedia.org. It contains a short article about the 1851 Monster Meeting at Forest Creek.

Read the eurekapedia article Monster Meeting at Forest Creek.