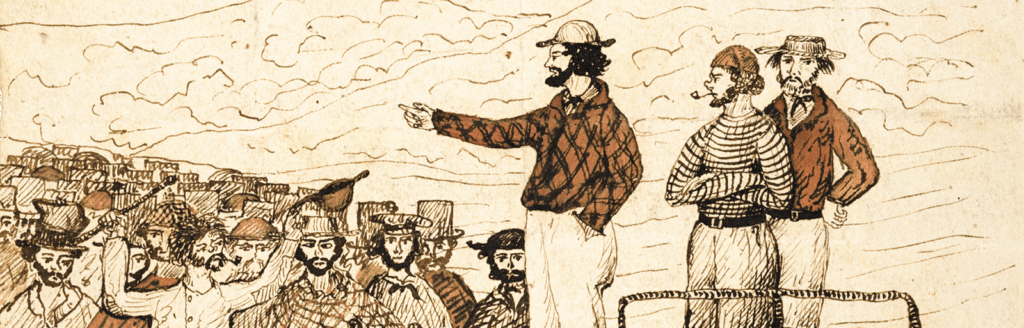

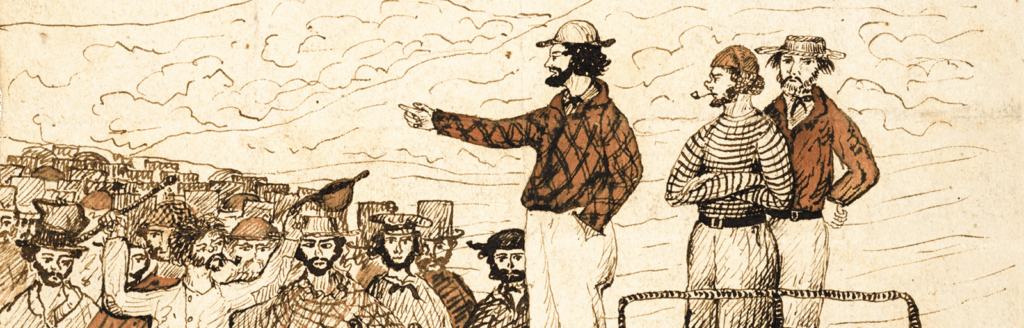

The Argus journalist, John Howard, was there to record the Meeting, including the rousing speeches from the dray. Howard’s full report of the Meeting, including the speeches, was published in the Argus on Thursday 18 December 1851 and is reproduced here. An unknown artist left us a pen and ink drawing of the speakers.

MEETING OF THE DIGGERS AT MOUNT ALEXANDER

Monday, 15th December, 1851

(FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.)

Early on Monday, preparations were made, flags collected, and a temporary platform brought to the spot in the shape of a dray, which being well secured, answered the purpose. As the hour approached, men began to collect in small groups along the Creek, and wend their way towards the appointed spot, and by three o’clock some eight or nine thousand persons had collected.

Hore’s band was heard in the distance, and as it approached large crowds made their appearance from the lower diggings, which were welcomed with hearty cheers.

Every preparation having been made, the Committee took their stand, and J. F. Mann, Esq.,was called to the chair, who stated the reasons why the meeting had been called, and trusted that the numerous crowd assembled would conduct themselves as became men. He then called upon Mr. Potts to address them.

On this gentleman’s appearance, he was welcomed with three hearty cheers, and addressed them as follows—

Brother Diggers and Fellow-Citizens;

This unrighteous proposition of the Government compelled me to appear before you on a former occasion. You all know what was said and done at that meeting and the decision come to, to call the present, and though I expected to have the pleasure of addressing a large concourse of my fellow-diggers, I must say I was quite un-prepared for the present assemblage.

I see before me some 10,000 or 12,000 men, which any country in the world might be proud to own as her sons. The very cream of Victoria, and the sinews of her strength.

Now, my friends let it be seen this day whether you intend to be slaves or Britons, whether you will basely bow down your neck to the yoke, or whether, like true men, you will support your rights. (Cheers)

On this ground are collected some 25,000 or 30,000 men, who have hitherto united in the bonds of friendship, discarded all distillation of nations and needs, and lived like brothers.

Why then should we bear a grievous imposition, while it is in our power to avoid it? You must be aware, that the 30s charged by the Government is an illegal taxation (not correct), and that His Excellency has no power to tax us.

We are willing to pay a small tax, but the question is, will we pay £36 a year? (Voices from all parts, never.)

Because a few men think proper to say, you shall pay, that is no reason why a body of men such as I now address, should accede to such extortion. (No, no, we will not.)

The Herald describes us as a set of cut-throats and scoundrels, from that journal little else could be expected, and I should not have brought this subject forward, but that I conceive there is something in the back ground. You all know George Cavenagh, and you may easily know, that the article was simply written to gain favour with Commissioners, and those who ride after the gold cart. (Good men.)

Now we want no favour from such good men. Talk of honesty! I defy the world to produce the same honesty among the same number as at Forest Creek. Is there one of you who locks your door. (Laughter.) When I retire to rest, the last inquiry I make of those in the tent is, whether they have put the skewer in the blanket. (Renewed laughter.)

Men go to work, leaving thousands of pounds in their boxes, without lock or guard, and nothing but a bit of calico between that and a robber, that is, if there is any. Do not fathers bring their daughters among us, husbands their wives and children, and where has there been a single case of one being insulted. You are living in better order here than they are in Melbourne, with all their blue coat force, pistols and carbines included.

It is useless to talk of physical force, moral force is what is required. You are men, possessed of the same power of reason, strength of mind and body, as your would-be extorters.

Now will you pay the £3 license. (Never, from all parts)

Good. Now my friends I tell you, that if you were sued for the 30shillings only, no Court in the British dominions dare give it against you; we are willing to pay a little, but skinned alive we will not be!

The Home Government does not require, nor do they possess the power to enforce unjust taxation. It was such taxation that lost Great Britain, America. I hope brother diggers, as a Briton, such unjust taxation will not be the cause of separating these splendid Colonies from the Mother Country.

But mind, if from any mis-government, the feelings and affection we at present possess as Britons, are torn asunder by Government misrule, and 50,000 British hearts are estranged by misrule— then, and then only, must violence be talked of. (Hear, hear.)

There are few here who would advocate separation; few who do not love the Country of their adoption; few who do not feel themselves Free! And none, I trust, who will be slaves! (Immense cheering)

I call upon you once more, to pledge yourselves to support one another – not only against taxation, but against disorder. We do not want the verdant youths of the Commissioner; they will do very well to rise after the gold cart- but, to keep us in order- why, men, the idea is absurd! We will see to one another. A Digger in distress shall raise a thousand brother-diggers, to support him.

This is the first chance the labouring classes have had to do good, but let them not abuse it. His Excellency is a squatter, a butcher, and he is interested in keeping down the price of labour.

They say, labour is too high, and men cannot be got. Why, I can employ a thousand men within a week. Let him pay a fair price; and he too will find no difficulty. Why should the laboring men be skinned alive, by what Sir Eardley Wilmot termed Wool Kings?

I will now read you the first resolution; seconded by J. O’Connor, Esq.

That this meeting deprecates as unjust, illegal, and impolitic, the attempt to increase the license fee from 30 shillings to £3. Carried

Capt. Harrison, with delegates from Bendigo Creek and other diggings, made his appearance on the platform, and was received with three hearty cheers. The Captain addressed them in a few words, thanking them for the flattering reception, and promised to have something to say when his turn came.

Mr Lineham rose to address the meeting, and commenced by stating, that he would occupy their time a few minutes with a small matter concerning himself.

You will remember, friends, that at the last meeting I drew your attention to the leading article of the Herald, wherein he kindly termed you the scum of Van Diemen’s Land, and many other opprobrious names. This has reached him through the columns of the Argus, and raised his anger against me individually.

He (George Cavanagh, Editor of the Herald) tells you, in his last leading article, that he has sent you an agent to watch over your interests, but I am more inclined to think it is for the purpose of looking after his own; and that I consider is very small, for I shall be much surprised if any man present will support the Paper which contains what I will read.

It was such men as George Cavenagh, and the lying Herald, that made peaceable men rebel against Government. (Mr Lineham then read the objectionable parts of the Herald’s leading article, which was heard with groans and laughter.)

Now, men, if George Cavenagh’s Paper is not a libel against the whole of you, I am not worthy of standing here.

Having satisfactorily proved to you that my former statements were true, I would now draw your attention to a subject of more importance. It is the tax. Will you pay £3? (No, never.)

That’s right. Now I will tell you how I intended to do, when the Commissioner came round. I should refuse to pay, and he would compel me to go with him. Now I should propose if one went, all went. (Yes, yes.) Of course we are too independent to walk, and it will take a curious number of horses to drag us to Melbourne. (Laughter)

I am not an advocate for forcible resistance, nor do I think any of you are; we can gain the day without it, though the Herald should use its thunders.

But, my friends, I find in the present number of that Government tool, that they have altered their mind. That they do not intend to enforce it, but to establish a royalty. Have we any assurance that such is the case? Or if such is the case, what guarantee have we that another change may not take place at the same breath?

I would advise, that until something definite is settled, pay nothing; it is the height of madness for Government to try the strength of a body of men like us, united as I believe we are; we can defy the whole colony put together if compelled to do so.

Some blame Mr. La Trobe for all this disturbance; now I beg to differ. Mr La Trobe has his faults, but I consider that he was too easily led by the advice of designing men.

I trust none will pay the £3 imposition or any royalty, though they were obtaining twenty-pound weight of gold per day. (Hear, hear)

He then read the second resolution, seconded by Mr Doyle, and carried:—

That this meeting while deprecating the use of physical force, and pledging itself not to resort to it except in case of self-defence, at the same time pledges itself to relieve or release any or all diggers that on account of non-payment of £3 license may be fined or confined by Government orders or Government agents, should Government temerity proceed to such illegal lengths.

Captain Harrison came forward, amidst deafening cheers, and as soon as he could be heard, said:

I am a little late, but you will bear in mind I have ridden 20 miles to address you. (A voice—”Put your cap on, Captain.”) I took my cap off, my lads, to honor patriots, but I might not do so for Victoria or her myrmidons. I feel proud to have it in my power to stand before such a noble set of men—men who will protect themselves against the oppression of an unjust Government. Why has Government made this change? They say it is to pay the expenses of protecting us, but I say, men, they are false pretences.

We might have our throats cut, our tents robbed or fired for all the protection Government affords us. How was it at Ballarat, when a serious row took place by a set of midnight scoundrels; when the lives and property of several were in danger, and expresses were sent to the Commissioner to send up the police, or that murder and robbery would be committed? What did Government do? What did the Commissioner say? I’ll tell you. He said—”I would send you the police with pleasure, but the truth is, I have not enough to protect myself.” What then are we paying for? We give a fee for protection, and get nothing in return. It is not the police protecting us, but it is we who are taking care of them.

There is now a surplus of £13,000, which has been screwed out of the sinews of the gold-diggers – (Shame, shame) – and what is to be done with it? They say it’s for the Queen. Has the Queen not enough, or does she want it to buy pinafores for the children? They will tell you her salary is small. I wish to God I had 1-20th for mine!

I called a meeting at Bendigo Creek the other day, and all came except the tent-keepers, to a man, and it was unanimously carried that we would not present an humble petition to withdraw the tax, but, like free and independent men, we decided that we would publish to the world, by every means in our power, our determination not to pay the tax.

A subscription was entered into to pay expenses, and every man paid his half ounce of gold. I was appointed a delegate to visit Forest Creek, and endeavor to cause the same feeling here, but I was proud to find on my arrival that you were beforehand with me.

Fryers Creek has not been behind hand, from 150 it has swelled to 3,000, a small beginning, but a small spark will blow up a magazine, or increase as your present number shows.

Talk of doubling the fee, let them reduce it one half of the present charge instead of doubling, or they will find, like the fable of the golden egg, that in grasping all, they will get nothing.

As for the statements of the Herald with respect to a royalty fee, it is only put in another and more obnoxious shape. They say that according to law the Queen is entitled to a royalty. The Colonies never cost the Queen or Government one shilling, and under those circumstances I consider that they are not entitled to the benefits of the land.

John Bull was a quiet animal, but if imposed upon, might do the same as the camel; he would stand quiet enough until they overloaded him, but if he got one ounce too much, he would kick until he kicked the whole load off, and threw his rider into the bargain. He considered the tax unconstitutional, and it was a similar tax that lost Charles the First his head; it was unjust taxation that caused the United States to throw off the burthen, and unless the Government learnt a little wisdom, an additional tax might lend to the same result here.

He knew he was rather warm on the subject, but he spoke as he felt, and he trusted all would do the same. He would not occupy their time much longer, but would wish to draw their attention to the support they had received from the Press, with the exception of one.

As to the lying Herald, whatever its proprietors might say, it was of little consequence, the journal was well known, it would crush all and every poor man, to exalt aristocracy. At first he professed to be the Catholic organ, they saw through his duplicity, and he, to save himself, panders with the Government. George Cavenagh put him in mind of the fable of the ass, who, when put between two bundles of hay, starved himself to death.

With respect to the squatter, he considered that class the worst used of any. They had been fostered up by Government for the purpose of preventing unity.

Let us, my friends, unite as one people (Great cheering) without respect to creed or country, and victory will crown our efforts. (It was some minutes before the next speaker could be heard, from the cheering.)

Dr. Webb Richmond proposed the third resolution, and observed that he had resided among the miners here and at Ballarat for three months — he had been associated with large bodies of men in various parts of the world, and had never in his life met with a better conducted, quieter, or honester set of men than the lucky or unlucky vagabonds of Mount Alexander; he had never experienced more kindly feeling or seen more exhibited than among the miners assembled, and what pretence the Herald could have for stigmatizing them as it had, he could not divine, and although quiet and orderly, the Government had done nothing out of the thirty shillings license money to protect them.

With regard to the said license, he did not consider the Government had any right to impose anything as a tax or royalty. These Colonies were vested in Parliament, and no revenue could be raised out of them except for the benefit of the people.

The Crown Lands Act appropriated the proceeds to the specific purposes of emigration and improvement, and if any surplus arose after paying the expenses of protection, to the Land Fund, &c., to no other could it legally be applied.

He doubted very much the wisdom of a license fee, it was expensive to collect, unequal in its bearing, and a perfect collection all but impracticable.

The Sydney Government had in hurry and consternation originated the system, and this Government had blindly followed it, without any substantial reason.

He was certain that not one-fourth of the diggers had paid license, or ever would, but the increased demand of £3 all were determined to oppose, not so much for the amount of the money, as the principle involved. If the Government obtained this increase, there would be no end to their demands, and they may depend on many increases.

He looked upon these measures as evidences of incapacity in the Government, and unless they did something towards governing themselves, they would inevitably fall into difficulties. They were in the condition of a large mercantile firm requiring good management, and they would find themselves compelled to a system of self-protection, and he should recommend an Association, having a joint-stock Bank, to issue notes, melt the gold into bars, assay and stamp it, and export to the best market the surplus not required as deposit, to secure the stability of the Bank.

They may conduct all their business themselves; but if they did not, preposterous as it may appear, they would find while gold was worth £3 17s 10½d in London, it would fall to £2 10s, or perhaps to £2 in Melbourne.

All sorts of schemes would be devised to operate on the diggers, and reduce their profits, while, if they united and acted wisely, they could not only protect themselves, but add largely to the commercial prosperity of the Colony.

He would now move – That Delegates be named from this meeting, to confer with the Government, and arrange an equitable system of working the Gold Fields. Seconded by Mr. Potts, and carried.

Moved, that Captain Harrison, Dr. Richmond, and Mr. Plaistowe be appointed Delegates from this meeting, to make arrangements with the Government in the spirit of the foregoing resolutions. Carried

Mr Booley succeeded the former speaker.

Fellow-diggers—If anything ought to cheer the heart of a man, and place him in society, it ought to make him glad. There are few people who properly understand what a Government is, or what it ought to be. It should be the chosen servants of a free people, and to be just they ought to be a right-minded people. To be respected by fellow man, is a right-minded man’s pride.

What ought to be the standard of man? Justice. Why do we cry out against Government? Because they do not do justice. Government ought to act with rectitude towards themselves. We ought not too readily to speak against Government. We do not wish to destroy the distance of a Government. We wish to look upon it as a beautiful picture, which that Government ought to represent.

I dare say you have seen a picture resembling a being with scales in one hand, and a sword in the other; the scales represent justice, and the sword represents the power of maintaining it. Such should be Government. A criminal, when brought to justice, hangs down his head and trembles but the innocent man stands erect, he asks no favor, and as equal man in estate, we ask but for justice! (Cheers.)

In America, the land sold, benefited the country. It caused immigration, repaired roads, and all and every part was fully and fairly accounted for. If Mr La Trobe has any foresight, he must see this tax ought to be appropriated to similar purposes and unfold the vast resources and manifest riches to the world. Why does he require it for the Queen, who will never receive a sixpence? Let him expend it to make the Colonies what they ought to be. Let him make it a Colony of virtuous and thriving people.

We have been told that the poor man is starving, that work is scarce, and they have nothing. Now the scale may be turned. The poor man may be elevated, the independency so much desired is within his grasp.

I could not but laugh, when, in Geelong, at hearing a friend of mine complaining, “Why, said a passer-by, do as I have done.” I went to the diggings – sank a hole – the next day I went down a poor man, and at night came out a gentleman. (Laughter)

Is it not as fair to give the poor man a chance as the squatter, when wool is up? Why should so much favour be shown them? What attention have they paid to the comforts of their men, – bad huts, bad food, and often bad treatment, while they were lolling in their mansions. Let the poor man get the value of his labour. If the rich would not give it, Providence, in his wisdom, has thought fit to do so. Let them make good use of it, and let them act on the great principles – morality – justice and truth.

They talk of the morality of Mr La Trobe in private life, but I unhesitatingly assert that Mr. La Trobe is an immoral man, in every sense of the word. Like the man who strained at the gnat and swallowed the camel, he lay the tax upon the people that were compelled to shear, sow, and reap, until he drove them to agitate. He finds his conduct deprecated, and that destruction must follow. He says we must let it pass; the people will endure it no longer, and thus he plays with their feelings.

Now, my friends, make up your minds; if you find a man who does pay £3 for his license, although he obtain 50 lbs. of gold per day, surround his hole, and prevent him working. (Long and continued cheering, accompanied with—we will, we will).

The Speaker then alluded to several instances, where men when combined, could do more with each other than the Government.

You, my friends, will not want to fight at all; make up your minds you will not pay; you may if united, defy all power. I wish distinctly and earnestly to beg of you not to let anything divide you; carry out your purposes; there is no danger, when a Government is corrupt in nature as this is. (Hear)

I trust you never, never will be slaves. Form associations, banks; let money out at interest. Should you, as a poor man, want money, pay interest. Out of this may grow importance, rich in mind, rich in morals—free and independent as we would be. (Cheers.)

Mr E Hudson came forward and told his numerous hearers, that when they had settled down he would say a few words.

Previous to my coming here this afternoon, I candidly confess I did not do you justice. I expected to find, as on most such occasions, numerous interruptions, with all the &c., but I must say, the greatest credit is due to all assembled, for the quiet orderly manner in which this meeting is conducted. You have effectually shut the mouths of your opponents, both blue and red.

Now I happen to be a short man, and not favorable to long speeches, and you can do a great deal in a short time, not by physical force, for I am not built for fighting or rigged for running, but by a firm determination to stand together, and support each other against the £3 imposition. Will you pay £3? (No, no, from all quarters.)

We will deal in suppositions, though they make but a poor meal for hungry men. Suppose Government send power. Will you stand firm? (We will.) Well, then, if the noonies do come, put them in your cradles and rock them to sleep—but mind, keep your powder dry.

When I came over from Adelaide, I had various opportunities of seeing what scarcity there was for labour – men could be obtained if fair wages were offered; this the settlers would not do, and the men came to the mines. Government wish to drive them back by a heavy tax, and compel them to accept the settlers terms; but I say, let the lazy, would-be-gentlemen, turn out themselves, or pay the price that gold will fetch.

Gold had no attraction, to leave picks, spades, and cradles, to come here to assert your rights. Be steady to your purpose, but as I said before, keep your powder dry.

The Speaker finished with once more entreating them to stand firm to their purpose, and if providence favoured them, to make good use of it on their return home.

The fourth resolution was then read.

That to meet the expenses of the Delegates and other incidents, a subscription of 1shilling per month from each cradle be entered into. Carried.

Captain Harrison then came forward to draw their attention to the necessity of enrolling themselves into an Association, each member to pay 6s entrance, for the purpose of meeting any demands at a future period; if not wanted, to be equally divided between Melbourne and Geelong, and devoted to charitable institutions.

The fifth resolution was then read, and carried – which was as follows:-

That the miners at each diggings appoint Committees to watch over their interests, and that a Central Committee be formed by a Delegate from the Committee of each Digging, such Delegates to be paid for their services, and report proceedings to a General Meeting of the miners, to be held the first Monday in every month.

As a Committee will meet at each of the diggings, and the various Committees meet together at places as may be agreed on, it is necessary now to select twelve parties; let them be divided so as to receive subscriptions and enrol their names.

Twelve gentlemen were then named by the meeting; and at the suggestion of Captain Harrison, Mr. Howard (Argus journalist who recorded the Meeting) was appointed treasurer.

Three cheers were then given for the Argus, which was heartily responded to, when Mr. Howard, as the agent for that paper, returned thanks in a few words. He sincerely thanked them in the name of his employers. He knew that it was ever the wish of the proprietors of the Argus to watch over the interests of the working classes. He had been sent there for that purpose, and until he might be recalled, should endeavour to the best of his ability, fearlessly and frankly to make his reports.

One cheer more for the Argus—three groans for the Herald, a vote of thanks to the Chairman, a tune from Hore’s band, and the immense crowds gradually dispersed to their respective tents.

At seven o’clock that evening no person could have surmised that anything of importance had taken place during the day. During Captain Harrison’s address, there could not have been less than 14,000 persons on the ground, not a cradle was to be seen working. The men appear to have risen en masse, at the sound of the band, and retired in the same order.